Thoughts on “Beginning of the Great Revival”

July 5, 2011 § 3 Comments

By Rebecca Liao

To celebrate July 4th this year, I saw Beginning of the Great Revival (or The Founding of a Party in the People’s Republic of China), a movie released last month by the Chinese government to commemorate the 90th anniversary of the Chinese Communist Party. While the film does not have anywhere near the level of propaganda in films from the Cultural Revolution, it would be hard to miss how badly the government wants people to buy into this movie. The state’s initiatives have a strange resemblance to the New Yorker’s offering Jonathan Franzen’s piece about David Foster Wallace to readers for free as long as they “liked” the magazine’s Facebook page. Only, Beginning of the Great Revival is not as seamless as Franzen in its presentation of a very complicated narrative. And even if people had read Franzen’s piece primarily to keep abreast of a Very Important Writer, the compulsion cannot be compared to being deprived Transformers: Dark of the Moon and Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows: Part 2 (on the big screen, that is: the former is already available on the streets in China and the latter will be available soon) until Beginning of the Great Revival grosses in the nine figures domestically. My seeing the movie in the U.S. was not going to help my people back home. But to indulge in a healthy dose of American irony with a side of Chairman Mao’s favorite raw, hot peppers, I ambled into the nearest AMC theater and took my place between an elderly Chinese woman who kept an excited running commentary and a little boy who really only showed interest during the assassination scenes. Here are my 8 lucky thoughts about the movie:

1) Seeing stars. Nearly all the A-list actors and actresses in China make appearances. Chow Yun-Fat as the delusional emperor Yuan Shikai, Liu Ye as Mao Zedong, Zhou Xun (Zhang Ziyi’s rival before Zhang decided dating billionaires was such a better business strategy) as Wang Huiwu, Andy Lau as Cai E, Fan Bing Bing as the Empress Dowager Longyu, and on and on. Coupled with the breadth of historical events covered and the expansive mise-en-scene, the spectacle was breathtaking and relentless, much like the opening ceremony of the Beijing Olympics. When it comes to mobilizing large numbers of talented people, China is second to none. Most of the actors and actresses waived their fees to be a part of this film. I hate to beat the we’re-losing-to-China dead horse, but can you imagine Brangelina or any American A-lister doing the same barring a highly-publicized natural disaster?

2) It’s weird to think of Mao as a human being. Chairman Mao as a passionate, earnest and capable leader is a time-honored (and probably pretty accurate) persona. Mao as a romance hero? Several Mao-glorifying scenes earned a smirk, but the subplot about his romance with his second wife, Yang Kaihui, whom he abandoned in real life to shack up with a 17-year old, was just cringe-worthy. She is charmed by his height and intelligence, he by her innocent, playful nature. On his deathbed, her father and Mao’s favorite teacher, Yang Changji, wakes from a coma and gathers enough strength to clasp the lovers’ hands together. This is just way too much cheese for a lactose-intolerant population.

3) Chinese history is complicated. Beginning of the Great Revival tries to cover the events from the Xinhai

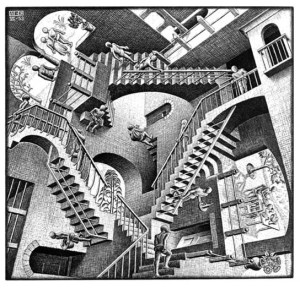

M.C. Escher’s Relativity (Source: http://evansheline.com)

Revolution in 1911 to the founding of the CCP in 1921 in just over two hours. Because the film is an officially sanctioned version of history, omitting any historical figure would fuel speculation about who is out of favor with the Party and what that means for the Party line. Labels that pop up as each person is introduced help, but the sheer number of players and the complexity of their political relations is still a challenge. Superficial treatment of most significant events was necessary but certainly increased the confusion. There’s nothing quite like this period in Chinese history. However, I imagine that if we condensed War and Peace into 200 pages without eliminating any characters and mapped them onto an M.C. Escher lithograph littered with land mines, we’d have something comparable.

The number between 3 and 5) Hots for the teacher. The Chinese lionize their scholars. On film (and in real life, to a certain extent), they are categorically hot. They are brilliant, charismatic, dignified, and passionate, with rhetorical gifts that produce witty repartee one moment and rousing revolutionary speeches the next. They’re also good looking. That’s all.5) Speaking of beating a dead horse. When will the story of foreign aggression grow stale? This is not at all meant to be a point of criticism: a depiction of the events leading up to the May 4th Movement must include the humiliation of having Germany transfer Qingdao and Jiaozhou Bay to Japan as part of the Treaty of Versailles. But to this day, foreign encroachment on Chinese sovereignty and general disrespect on the international stage are the sorest spots in the Chinese psyche. No doubt they have been a great source of motivation to develop the country as quickly as possible, but now they serve mostly as demagogical levers for the government. China has essentially become a capitalist country. As is the case for every successful startup, the narrative has to go from, “We have come so far,” to, “Where are we going next?” High-speed railways, longest bridges in the world, the lone spot of economic stability as the rest of the world founders—these have been on every pundit’s list of talking points in the past year. China has captured the world’s imagination; how does it grow its soft power? First thing’s first: step out of the shadow of rapid ascension and embrace sustained change and growth.

6) Speaking of soft power. AMC Theaters inked a deal with China Lion Film Distribution to exclusively distribute the film in North America. In the U.S., it is showing in 29 theaters, all in the Chinese immigrant hotbeds of New York, Los Angeles and San Francisco. While this movie will never be an Oscar contender, it is interesting to see how it stacks up against the box office performances of the last five Academy Award winners for Best Foreign Language Film, the most recent three of which enjoyed the press of the win and two of which received positive critical attention in major domestic publications when first released. On average, they grossed $115,394 in their opening weekends and had a ranking of 39, but were only shown in eight theaters. By contrast, Beginning of the Great Revival grossed $65,866 in its opening weekend and ranked 37th, but is playing in 29 theaters. There is a certain appeal to the regular art house film crowd of a stylishly filmed propaganda movie, but let’s be honest: AMC was betting that blood would be thicker than water. We’ll have to wait until the end of the movie’s run for a final verdict, but it looks like the Chinese are actually quite good arbiters of quality.

7) Do not try this at home. The irony of a government-sanctioned film commemorating a revolutionary response to injustice and oppression was not lost on the mainland Chinese audience. If anything, though, the irony serves more as a reminder of the government’s power than as motivation for demanding reform. Still, the first step towards legitimizing a social movement is to glamorize it: the government should be careful what it wishes for.

To get you in the mood for number 8:

8) The East is Red. In a desperate attempt to regain political clout ahead of China’s imminent leadership transition, “Chinese JFK” Bo Xilai instituted a campaign to revive Red culture in Chongqing, where he is mayor. The charm offensive directed at Beijing includes sing-a-longs to Red songs, Red song singing competitions, and readings of Mao’s poetry.

Surprisingly, not everyone is laughing. It turns out there is significant nostalgia for the days of Chairman Mao, not because anyone longs for famines or the Cultural Revolution, but because there is something about Red culture that the Chinese feel proud to claim as part of their DNA. The revolutionary impulses in the film that the government is trying to promote and suppress at the same time have free expression in Red songs. This is true for many people in mainland China, but all the more so for the workers and peasants that are the songs’ heroes. Chairman Mao rose to power off of the widespread anger and fatigue of the working class—perhaps his rehabilitation is not so much an exhortation for the newly wealthy Chinese to remember his ideas as it is a reminder that his ideas have not been forgotten by the CCP. Altogether, now:

If you look at the amount of movies that are officially endorsed by the US military machine then I guess this pales into comparison. Of course, when America does it, it’s entertainment and entrepreneurial individuality, when China does it, it’s propaganda.

The fact is, love them or hate them, the Communists have power in China and they are a government, which means they can get people to do things. The West no longer has governments, they have a rich minority that tell governments what to do. Look at poor Obama. He couldn’t pass a bill to let himself go to the toilet.

I agree there are innumerable American films glorifying war and the US military, but the government does not directly fund those films. The Chinese government was both the financier and guiding hand for Beginning of a Great Revival.

Thanks for reading, Darren!

There is no difference between propaganda that is funded directly by the government and propaganda funded privately by institutions more powerful than the government. That was my point. Interesting article, though.