Recognize the Republic of China

July 28, 2013 § Leave a comment

At a symposium held at the end of April, Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) deputy Jen-to Yao, thought to be a reliably strident advocate for Taiwan’s independence, sharply criticized his party’s central independence ideology. In response to the controversy that followed, Yao clarified in an online essay that while he was not giving up the fight for Taiwan’s sovereignty, he realized that the strategies and methods in service of the movement needed to change to fit the times. Yao proposed instead that independence supporters push for Taiwan to establish formal diplomatic relations with the People’s Republic of China.

But, wait. Diplomatic relations with the PRC—which means that the PRC would have to first recognize the Republic of China (on Taiwan) as a legitimate state under international law. One might think: How is this any less of a fantasy? The PRC goes into a fit when a third state threatens to recognize Taiwan. What incentive does it have to break its own rule? Doesn’t the PRC adamantly reject notions of “two Chinas,” or even “one Taiwan, one China”?

Very simply, though, it is in the interests of the PRC to recognize the ROC.

If China envisions “peaceful coexistence across the Strait and a concerted effort towards a unified nation” with Taiwan, then normalizing relations with Taiwan is the PRC’s best option. Leaders in Beijing can make a generous offer: “The PRC and the ROC recognize each others’ sovereignty as legitimate states under international law, but as members of the same Chinese nation, the two sides commit to fulfilling a specific unification timetable.” Basically, the deal offers current independence with eventual unification. The PRC could then effectively lock in the status quo, wipe out Taiwan’s independence movement, initiate an actual unification timetable and gain a new ally in the Pacific. For the PRC to recognize the ROC, however, it still needs to hop over the psychological hurdle of “One China.”

China’s attitude towards Taiwan has long been based on the dogma that “there is only one China, and that one China cannot be split.” Taiwan, to hang on to an existence separate from the Mainland, has come up with many compromised interpretations of that dogma. The current state line is the so-called 92 Consensus (which, according to Taiwan anyway, states that “both sides agree there is one China but disagree on what ‘China’ is,” but China conveniently drops the latter half about disagreeing). President Ma’s administration has translated this as “mutual non-recognition of sovereignty but mutual non-denial of jurisdiction.” The essence of this very acrobatic phrase is that while the two sides do not recognize each other as states, they have to accept the reality that the two governments operate independently of each other. Even though China has not responded directly to this stance and officially rejects any deviation from its dogma, it effectively bases its interactions with Taiwan on this framework.

The key assumption of the status quo is that a nation is defined by sovereignty. If China is a single nation, its sovereignty cannot be split into two. However, this formulation is disingenuous because the Chinese concept of “nation” (guojia) is actually different from the Western idea of the sovereign nation-state. Under the nation-state system, a state is merely a government that holds the allegiance of people living within a specified geographic border. In exchange for the perquisites of being a part of the international legal order, the state upholds its responsibilities within that order.

On the other hand, the idea of Zhongguo for the Chinese is a more expansive concept. China’s imperial history has tolerated periods in which multiple states existed within what we consider to be “China” today. These states exercised independent sovereignty and exchanged diplomats even while vying to be the eventual unifier. What drives the Chinese concept of guojia is not just the institution of the state, but also the emotional and cultural connections that goes beyond political boundaries. Therefore, when the PRC clumsily equated Western style sovereignty and jurisdiction with the idea of the one Chinese nation, it unnecessarily obstructed itself from resolving the Taiwan question. Based on historical traditions, the PRC and the ROC can mutually recognize each other’s sovereignty without contradicting the idea of one China.

After overcoming this psychological barrier, the PRC can immediately reap the benefit of not having to live a lie. By continuing to insist that both sides (tacitly) agree to separate jurisdiction without recognizing sovereignty, the PRC perpetuates some absurd gaps between fantasy and reality. President Ma Ying-jeou, who was elected by a wild majority of the Taiwanese people, lost sleep on what PRC officials could call him (Mr. President? Mr. Chairman? Mr. Ma?) on official visits to Taiwan. Tourists on both sides just wanted to enjoy the scenery in Guilin or the oyster omelettes in Shihlin but had to put away their official passports and spend more money just to get a “passport that is not a passport”. President Ma is now pushing for representative offices on both sides. He says, “the offices will offer all the services of embassies, but I have to stress that they are absolutely not embassies!”

Please, is this really necessary? Questions of political symbolism aside, when the two sides refuse to acknowledge the reality that jurisdiction must mean sovereignty, normal relations retreat to ground zero and never emerge: what to do with “official representatives that are not official,” “foreign laws that are not foreign” and all such ridiculous, unnecessary exercises. If China were to recognize Taiwan, the two can deal with each other as two normal states, with its agreements in full force under international law.

The second benefit for the PRC is that it will finally be able to handle those in Taiwan who support “independence” over the “status quo.” Much of the Taiwanese people believe that the status quo is independence, and they want this current independence to be respected. At a fundamental level, the Taiwanese people, regardless of whether they look forward to independence, support the status quo indefinitely, or dream of unification, can all agree that they, at the very least, desire respect from the PRC. If the PRC unequivocally recognized the ROC, wouldn’t that satisfy the majority’s desire to be respected, and erase the independence movement’s main appeal? The movement would then be reduced to calling for an outright revolution to topple the ROC regime—which, despite past grievances, will only become less reasonable as long as the current government continues to operate through proper liberal democratic processes. If the PRC recognizes the ROC, this locks in the legitimacy of the ROC government and eliminates the need for more radical independence ideologies.

After the PRC fulfills Taiwan’s need to be simply respected, what is left for the two sides to talk about except unification? Once the PRC recognizes the ROC, I believe the two sides will sooner or later begin unification negotiations. For the PRC will have shown an amount of goodwill so great that Taiwan must respond in kind. After mainstream independence vaporizes, the pro-unification agenda should dominate public discourse. Furthermore, as China adopts a respectful stance towards Taiwan, the cultural, linguistic and blood ties between the two should naturally bring them closer together. In the era of regional consolidation and free flow of goods and labor, how can two states that share so much history and commonalities not be expected to merge? It is also good news for the international community for the two states to drop hostilities and peacefully agree to unify.

Finally, a China that actively normalizes relations with Taiwan will be seen as mature and responsible. For US-China relations, this removes a large bargaining chip the Americans have played for years: the US could no longer use Taiwan to extract favors from China. Taiwan will also no longer need to keep buying weapons from the US as threats from China simply disappear. The Taiwan lobby in Washington will also no longer be able to argue for “Taiwan’s peaceful self-determination”. All these developments would change the geopolitical map in East Asia in China’s favor by increasing its goodwill in the region while denying the US a close ally.

How should the Taiwanese public react to a deal like this? The most fundamental supporters of the ROC’s legitimate claim over China will not like this, since this forces them to accept the PRC as a state and its rule over the Mainland. However, this is a fringe opinion in Taiwan that requires an even more schizophrenic separation between fantasy and reality. Any pro-unification supporter would likely be in favor of this deal, but for moderate unificationists the question will be what conditions to require of China for eventual unification. Should the PRC democratize? Decrease its wealth gap? Strengthen rule of law? If these demands seem quixotic now, imagine the reaction if they were actually made.

Radical independence supporters will obviously reject any such proposal that legitimizes the ROC, but the moderate independence supporters, those who assert that “ROC sovereignty is independence,” will have theirs goals fulfilled. But what to do with the unification timetable? Would they accept eventual unification in exchange for a limited period of independence? If so, how long should this period be? 50 years? 10 years? Even three years? The pro-independence camp must have better answers to these questions, including what conditions (if any) are required for political talks, the fundamental definition of independence, and how Taiwan should conduct itself after it earns de jure statehood.

One may notice that on the issues, moderate pro-unification and pro-independence supporters are actually on the same page. Why not sit down and hash some of these answers out together?

Also in April, former KMT spokesperson I-hsin Chen published an op-ed in the South China Morning Post, directly calling on PRC President Xi Jinping to “confront the existence of the Republic of China,” and that “if both sides cannot reach a consensus over this…there will be no consensus on anything.” Although he stopped short of saying anything politically incorrect, it was clear to all regular observers that he was calling for the PRC to formalize relations with the ROC. Prof. Xu Bodong of Beijing Union University’s Taiwan Reseach Institute also recently said that “cross-straits consolidation may produce a new Chinese state with a new name, a new flag or even a new national anthem,” which implies that the concept of “China” exists beyond just the current states of the PRC and the ROC.

For too many centuries, China and Taiwan have had a twisted and perverse relationship. Wouldn’t all parties be better off speaking to the desires of the Taiwanese people to be respected before pushing for overall consolidation? In this way, China would not simply be the Western concept of a nation-state, but something that is longer lasting, more encompassing, more worthy of the aspiration of the people across the Strait.

This piece originally appeared in the Taiwanese magazine Commonwealth and was translated by the author.

Grading President Ma Ying-Jeou

May 2, 2013 § Leave a comment

“Taiwan is a responsible stakeholder and a peacemaker in East Asia. Taiwan’s democratic experience is a model for China, and we have long been a friend and ally of the United States…”

President Ma Ying-jeou had just concluded his remarks over videoconference amidst applause from the audience at Stanford University. Former Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice, the moderator of the evening’s proceedings, thanked the president and the participants.

Behind the lectern where Ma spoke earlier—most likely a room in the Presidential Office—the seal of that office hung above the words “Republic of China (Taiwan).”

* * *

People unfamiliar with Taiwan probably have good reason to hold President Ma Ying-jeou in high esteem. As Ma mentioned in his speech, which he delivered in his usual, mellow Confucian-scholarly style: “There were two flashpoints in East Asia, and while the world is focused on one of them right now, the other one has disappeared.” He is referring to, of course, the Korean Peninsula and the Taiwan Strait. Looking at the Taiwan Strait, over the very same waters into which ballistic missiles were fired as recently as 1996, more than 600 direct commercial flights now fly weekly, shuttling investors, tourists and exchange students. China has gone from Taiwan’s largest military threat to Taiwan’s largest trading partner, surpassing the United States and Japan in 2005 as well as becoming the only country to conclude a bilateral trade liberalization framework agreement with Taiwan. The people on both sides never dreamed of possibly exchanging postcards one day; today, pro-independence leaders in Taiwan have their own social media accounts in China (which were rather swiftly banned, but no victory is too small). Not a few magazine articles in the U.S. painted Ma Ying-jeou and his administration as one of the most important and creative peacemakers in the 21st century.

If this were true, I for one certainly welcome this brand image for Taiwan. Shut out of most major international organizations, including those under the United Nations, the Taiwanese people have long thought of ways to make themselves visible and recognized by the world. Imagine down the road—a Taiwanese leader receiving the Nobel Peace Prize for successfully defusing tensions between Japan, the United States, and China over oil rights in the Western Pacific by engaging the leaders in a series of four-way dialogues. Maybe Taiwan and China could come to a permanent peace accord that secures the independence of Taiwan’s way of life and China’s sense of national unity. Or Taiwan acting as the unofficial ombudsperson of East Asia, mediating conflicts stretching from Russia in the north, to New Zealand in the south. At Taiwan’s suggestion, Asian economies cooperate to build new standards in finance, capitalism and social order, based on ancient Asian principles of mutual respect. On that day, people will be proud to be called Taiwanese.

But let’s come back down to earth for a bit. This fantasy would no doubt be great for Taiwan. Is it, however, just a fantasy? Is Ma Ying-jeou a real visionary, or is he living in his own naïve la-la-land?

For one thing, when Prof. Rice asked Ma whether growing closer to Taiwan is a positive move for the U.S., Ma stressed that Taiwan-U.S. relations improve whenever he reduces tensions between Taiwan and China. This understanding of the US-China-Taiwan balancing act is rather juvenile. Indeed, in the years prior to 2008, tensions between Taiwan and China were at a high point, causing alarm for the United States. The U.S. did not want war to break out, as it would likely need to jump into the conflict to retain its position and allies in the area. Chen Shui-bian, president at the time and member of the pro-independence party in Taiwan, was chastised by the Americans for acting like a kid who kept poking the tiger just to see what’ll happen. Therefore, it is understandable that the U.S. would like tensions to subside—which Ma pretty much accomplished simply by getting elected, since his pro-China party would by no means be any more provocative.

Any further warming of relations between Taiwan and China, I believe, should be evaluated case by case where American interests are concerned. Favored trade treatment, or high level joint military meetings, is certainly tying the two sides closer; but as the U.S. is ramping up competition with China over trade and security concerns, Ma’s policies may very well bring sparks of uncertainty to American objectives in East Asia. Furthermore, after five years of the détente of “easy topics first,” China is running out of patience for Ma to get talking on the harder topics of political and regulatory integration. The pace of Taiwan-China honeymooning has already alarmed some in the States to the point of advocating for simply dropping support for Taiwan. The more politically and militarily integrated Taiwan is with China, the harder it is to keep asking America to see Taiwan as simply a friend and an ally.

Likewise, portraying Ma to be the peacemaker across the Taiwan Strait might just be giving him too much credit. The series of changes in China policy by Ma’s administration, such as opening up direct flights, allowing for exchange students and tourists, etc., could at best be described as a reversion to the mean—any two non-hostile states would have all of those things as well. They are not exactly “improving” relations, so much as “repairing” relations, which in reality had already begun under the previous DPP administration. In other words, they have picked the low-hanging diplomatic fruit. As I mentioned above, Ma’s real test is just coming around the corner, when he has to balance dealing with deeper integration with China on the one hand, and being on the American side of the Western Pacific power partition on the other.

More importantly, standing in the city alleyways or the edges of rice fields in Taiwan, Ma and the KMT’s policies of economic liberalization feel more like the product of short-sighted, profit-driven capitalists in fear of being left out of the China gold rush. Yes, many Taiwanese small businesses are better off today thanks to Ma’s policies. But the vast majority of the value created by cross-straits liberalization has been gobbled up by a small group of large corporate interests and their investors. Many large, profitable Taiwanese companies like Foxconn are built on exploiting the draconian labor conditions in China. Taiwanese real estate prices have skyrocketed in a bubble caused by Chinese speculators with the government abusing eminent domain powers to steamroll over old neighborhoods at the request of developers. The administration has been dumbfounded about whether pro-China interests can freely buy up news media. To the Taiwanese, opening up with China has not brought the economic paradise that Ma’s administration promised. Instead, it gave birth to a vicious profit-mongering snake, exacerbating the wealth inequality in both societies. President Ma is either too naïve to see that these are the results of his well-intentioned neoliberal economic policies, or he is knowingly working as a faithful servant to this predatory monster.

On screen, President Ma Ying-jeou looked so proud of his accomplishments, like a third grade student of the month taking photos with the principal. But does he know that the principal has already started to have doubts about him, that he might have gone overboard with his assignment to calm the paranoia in the Taiwan Strait? Maybe he does know. Forging an accord for fishing rights near the Diaoyutai/Senkaku islands with Japan might be a subtle shift towards the U.S.-Japan sphere of power; at least Beijing for sure is not going to congratulate Ma anytime soon for “settling sacred Chinese territory” with the enemy. The so-called “agreement” signed by a rebellious provincial leader is not enforceable, obviously.

Going forward, I support wholeheartedly the principle of finding common pragmatic values, and I support the vision where the world looks to Taiwan as a wise, mature advocate of peace, not just between states but within our interconnected societies as well. President Ma Ying-jeou has helped to reduce the probability of imminent war between Taiwan and China. But in that process, he has set Taiwan on a course towards uncharted waters—continued integration with China that will pull Taiwan out of American interests and unleash unforeseen catastrophes onTaiwanese society. Can President Ma or his successor leaders steer Taiwan through these torpedo-laced channels? Best of luck to them.

Taiwan Should Abolish the DPP and the KMT

May 2, 2013 § Leave a comment

Committee meetings in Taiwan’s Legislative Yuan are usually held in small conference rooms at the parliamentary courtyard, a cluster of old buildings that used to house a girl’s high school when the Japanese ran the show. On a hot afternoon in 2006, approving a big purchase of weapons from the United States was on the agenda.

Out of the blue, the right honorable member of parliament Li Ao walked to the lectern and began spraying tear gas into the air, disrupting the proceedings. Pandemonium broke out as the room filled with noxious fumes, and the highest representatives of the people scrambled for fresh air. This incident stands along the many other fistfights, shouting matches, and other such closing acts of Taiwan’s biggest circus, its legislature.

People who are not from Taiwan often marvel at its so-called “democratic miracle”—that is, how can such a friendly, hospitable people elect the goofiest and most immature political leaders? Similarly, the people of Taiwan ask themselves, where did things go wrong?

To correctly diagnose the problem, one must understand that Taiwan’s democratization story is part of a much larger one. It can only be completely understood along with Taiwan’s story of “independence versus unification,” or more precisely, the question of Taiwan’s national identity. As a result of Taiwan’s turbulent history, two competing national identities coexist in Taiwan. Democratization was a strategy that allowed both sides of the national identity conflict to wage war in a more civilized, air-conditioned setting, inside the halls of politicians and off the streets of protestors. Therefore, to induce Taiwan’s democratic governance to be more efficient (both in representing the myriad of societal wishes and in delivering on administrative promises), we must look at the problems brought on by the national identity conflict side of the equation.

A quick overview of the conflicting national identities in Taiwan can never give enough justice to the centuries of history they represent, but it is roughly as follows. On the one hand, some identify with a Taiwanese ethnic nation. It can be traced back as early as Taiwanese elites’ calls for higher degrees of self-rule within the Japanese colonial empire in the 1920s, which stemmed from their identifying themselves as a different entity from both the people on the Chinese and Japanese homelands. Later, a bloody and tragic clash of Taiwanese locals and the new rulers from China in 1947, and the social pressure of having to absorb an entire refugee society after 1949, added to the urgency of a strong Taiwanese state. The transplanted Chiang Kai-shek military one-party government did themselves no favors by crushing any bud of dissent. All these experiences produced a defensive identity for a nation that, at its purest form, is a people deserving of its own state under the 20th century classic notion of self-determination.

On the other hand is a national identity, identifying with a republican, unified China encompassing all that could possibly said to be Chinese, realizing the dream of 19th century reformers and revolutionaries led by Dr. Sun Yat-sen. The dream went into full force as democratic revolution became the solution to imperial China’s corruption, backwardness and powerlessness against modern Western colonialists. After a long series of crushing blows to the project by ambitious strongmen, warlords, carpetbaggers and incompetent officials, the republic endured almost a decade of desecration by the Japanese but finally surrendered power to the Communist Party. The years of war scorched much of the land, and those who fled the mainland to Taiwan were separated from their families and roots, in many cases permanently. The democratic China project lies at the bottom of this well of history, tarnished and unfinished.

In Taiwan, the responsibilities of achieving these two conflicting national identities have fallen on the two major political parties, the Chinese Nationalist Party (the KMT) for “Republican Greater China” and the Democratic Progressive Party (the DPP) for “Self-Determined Ethnic Taiwan.” Of course, the two nation-building projects have long predated the formation of either political party. But as the nation-builders organized, they realized that for them, nation-building necessarily meant state-building as well—taking over the power of sanctioned authority. This was the case for the KMT in the 1920s when the first Chinese republican experiment failed at the hands of Yuan Shikai; it was also the case for the DPP in the 1980s when they were formed to oust the authoritarian KMT government. In other words, both the KMT and the DPP are less governing political parties and more revolutionary nation-building organizations at heart.

And herein lies the problem with Taiwan’s democracy: two nation-building projects are vying for control over the same state apparatus. Between 1945 to 1987, the Republic of China government in Taiwan was a one-party martial law state controlled by the KMT. It continued its nation-building project in Taiwan, forcing on the populace an identity that did not match that of the majority of its citizens. This further consolidated the nativist Taiwanese self-determination cause, which contributed greatly to the anti-government and pro-democracy sentiment. In the 1980s and 90s, mass anti-government protests led the KMT to allow the opposition to enter national elections—the two sides chose democratic competition and compromise as the dueling ground, rather than violent revolution. The result for the previously seditious independent Taiwan project is that while now legitimatized, it had conceded the opportunity to eradicate and outlaw the republican Greater China project. The two camps therefore agreed to continue the fight in the parliament and through election campaigns.

This arrangement certainly produced an immense benefit for Taiwan’s society; that is, the costs of all-out military revolution had been avoided. But throughout the next few decades, this arrangement created structural strains, both on the actual need for Taiwan’s society to consolidate a workable identity inclusive for all its members, and for the daily functioning of Taiwan’s governing institutions. On the front of consolidating a workable identity, the current situation allows top-down nation-building along outdated and contradictory models to persist and encumbers transitional justice for the victims of martial law under Chiang Kai-shek. As for improved functioning of Taiwan’s governing institutions, the current situation burdens pragmatic considerations in Taiwan-China relations and immobilizes the political process’s ability to deal with pressing domestic issues such as development, distributive justice, and social welfare.

So here is a modest proposal to Taiwan’s civil society: abolish the KMT and the DPP, and rebuild a spread of political parties along ideological and issue boundaries. Let there be labor parties, environmental parties, parties representing free market capitalism and parties representing social democracy. Let the people who agree on how governance and the governed should interact from the KMT and the DPP get together and work towards their goal. Let the spectrum of political parties reflect the spectrum of issues and wishes of the voters.

Okay, maybe that’s a bit of a stretch. The KMT and the DPP are probably here to stay. It would be hard to imagine a social force great enough to pressure both parties into committing political suicide and giving up its infrastructure and core supporters. The national identity question will still remain and seep back into politics. Fortunately, both the KMT and the DPP understand that the political tectonic plates are indeed shifting. Student movements of recent years have sprung up in response to the mistreatment of old factory workers, violent removal of residents for urban renewal projects, monopolization of news media, and nuclear energy policy. Beijing has been pushing for more complex, intertwined regulatory, trade and legal modes of interaction beneficial to its side. All of these issues demand both parties commit to a clear stance, and more importantly, to a clear ideology so people will know what to expect in the future. The two parties will not have to merely adjust their policies, but think hard about their legacies and organizational power structure as well.

There is a lot of soul searching in the horizon for Taiwan’s two major parties. A lot of work still needs to be done if the people of Taiwan want to replace politicians weaned on nationalistic fervor with those that are pragmatic in their approach and empathetic in their service to the people. Perhaps then we will see Taiwan’s parliament as less of a circus and more of a proper, respected arena where a small committee meeting might just produce a small glimmer of optimism.

Concept of “Chinese” Predicated on Revenge

March 12, 2013 § 4 Comments

I recently wrote a piece on China in this magazine entitled, “We the People’s Republic of China.” In it, I present imperial China as a highly functional cosmopolitan empire built on philosophy rather than an ethnic nation-state. From that reading of history, I suggest that China rethink the legitimacy of its current political arrangement and the fervent nationalism on which it is based.

But is that the only way Chinese history could be interpreted? The Chinese empires ruled over people of many creeds and colors, and their policies had certainly not been tolerant. The Yuan and Qing Dynasties established caste systems segregated by ethnicity; non-Han ethnic kingdoms such as the Jurchen or the Dali were summarily brushed off as anomalies and footnotes. The Confucian examination system itself could certainly be thought of as a destructive force unleashed by the Chinese hegemon on its conquered peoples. Confucianism as it had evolved in China was a way to organize society, placing each person in specific social roles with rigid expectations and responsibilities. Advancement through mastery of the system, then, really meant internalizing and perpetuating those social hierarchies. It is not so different from the French government’s turning Bretons and Basques into Frenchmen through compulsory public education in the late 1800s. If we read history that way, China’s nationalism isn’t a 20th century phenomenon. It’s only the latest iteration of a millennia-old nation-building exercise.

Read that way, imperial China looks exactly like a modern nation-state. It encompassed an ethnic majority plus an influx of minorities and foreigners. It ruled over many aspects of its subjects’ lives through an advanced degree of systematic bureaucracy. It enshrined political stability by homogenizing the populace. The difference is that in the past, peasants and merchants became gentry subjects of the emperor through scholarly indoctrination, but today the nation-building project is predicated on rectifying the humiliation by Western powers.

In other words, China today is predicated on a psychology of revenge.

Which, fundamentally, is the pathology of China’s current strain of nationalism. It focuses on economic and military competition with its neighbors and the West, creating unnecessary tension; it allows for improbable wealth disparities within the state; it is blind to the harms done to minority ethnic heritages by its modernization policies; it necessitates a harmonious and united society over a candid and self-critical one, all as calculated costs for a singular end.

Giving due recognition to China’s cosmopolitan past and the accomplishments of the many nations within China is a first step (albeit already herculean in itself) to tampering this pathology, and many states today offer lessons of success and failure on how to manage ethnic tension within the institutions of the state (federalism, consociational forms of governance, etc). But we are only talking about a part of the problem.

So questions remain: Can China’s cosmopolitan past give us any clues as to how we got here, and what alternative paths China may take? Under what circumstances will China say, we have finished our project of overtaking the West, we have been paid our retribution in full? And once that happens, what will, or should, China become? I will attempt to offer my thoughts in future pieces, and I hope they will at least provoke more reflection on these questions.

We the People’s Republic of China

January 24, 2013 § Leave a comment

Some years ago, it seemed like every tourist visiting China was on the lookout for the same souvenir: the canvas bag emblazoned with the words wei renmin fuwu, “Serve the People,” in none other than Chairman Mao’s own handwriting. Was it the nonconformist symbolism of the Chinese Communist propaganda style that caught the foreigners’ eyes? Or was it the historical significance of Chairman Mao’s words that resonated? Who knows, and no one really cares. Not to the Chinese, anyway, as long as money is to be made.

Except the Chinese do care about what the word renmin means. There is China’s formal name, Zhonghua Renmin Gongheguo (中華人民共和國, “The People’s Republic of China”); Renmin Univeristy (人民大學); China’s legislative venue the Renmin Dahuitang (人民大會堂, “The Great Hall of the People”); China’s high court the Zuigao Renmin Fayuan (最高人民法院, “The Supreme People’s Court”), and on and on. Renmin translates into “people,” here used liberally to denote the members of the classless society established after the proletariat revolution, as if the people need some sort of constant reminder that the government belongs to them (nominally, anyway). Point being, the concept of the renmin goes back deep into the origins of China.

Renmin is made up of two more basic parts, ren and min. Just to confuse our non-Chinese readers, ren, min, and renmin can all be translated as “people.” Good people, bad people, tall people, short people, French people, indigenous people, etc. However, the connotations between ren and min are distinct. Ren denotes individual persons, describing a person as just him or herself, closer to the concept of a “human being” in English. A good person is a haoren; a benefactor is a guiren, a beauty is a meiren, and so forth. Hanren, is the Han ethnicity. Zangren, Tibetans. Ribenren, Japanese. Min, on the other hand, refers to a group of people under political rule. The Chinese word zimin literally means a prince’s people, or the English word “subject”; nanmin means people in crisis, or “refugee”; gongmin means people in public, or “citizen.” The people denoted by min is more like “We the People” with the capital P.

Perhaps, then, we can say, the Chinese language differentiates between “people” as simply a group of persons with distinct identities and characteristics, and “people” as one collective body subject to a common political fate. In other words, the people comprising a “nation” and the people under a “state.”

This offers some clues as to how China thinks of herself as a nation, a state, and a nation-state. The Chinese usually like to think of themselves as one nation and one state since the beginning of time. When a Chinese person talks about his heritage, it’s not uncommon to mention China’s “5,000 year history” and all Chinese being “heirs of the dragon.” However, beginning with the Qin Dynasty and much more so in the Han Dynasty in 206 BC, China was already an empire encompassing all sorts of ren—a variety of nations under one state. The state came first through war and continued to preside over a mixture of ethnicities and tribal clans.

To rule over all these different ren, the state must turn them into min. The Han rulers established a system of imperial examinations, through which social advancement was based on mastery of Confucian thought. This effectively established one philosophical and political system of thought for the entire populace, not just by brute cultural assimilation (though there was certainly no shortage of that) but, more importantly, by political indoctrination. Throughout China’s history, the imperial examination system had been one hallmark of all of the dynasties that ruled China. This includes the proud cosmopolitan dynasties like the Tang, the Song and the Ming (partially anyway), but also the non-ethnic-Han dynasties of the Yuan and the Qing. We may not be sure whether the people living in southeastern coastal areas felt a cultural connection with those living near the northern deserts, but they were all hoping to secure a seat in government and a mansion in the capital by taking the test. In this way, the succession of empires in China conducted nation-building within their borders, but I would argue that up until the end of the Qing in 1911, China was not a nation-state. It was much bigger than a nation-state.

Certainly, during the turn of the 20th Century, when ancient Asian empires clashed with modern European nation-states, China had to avoid the fates suffered by the Ottoman Empire (which shattered into many pieces) and India (which became a colony under a European power). Through violent revolutions, China guzzled up Western ideologies and tried to masquerade itself as a singular nation-state. Sun Yat-sen himself envisioned a purely ethnic Han nation-state in the beginning and only later acquiesced to “Hans, Manchus, Mongols, Uighurs and Tibetans” as part of the “Chinese nation.” Thus, in an utterly hasty fashion, a new nation-building and a new state-building project began in the ruins of the old Qing Empire. The process was anything but civilized (just ask the Tibetans), but the means justified the ultimate end: to create an united front in order to vindicate the humiliation suffered at the hands of 19th Century imperialists.

In 2013, after every Western ideology has run its course in China, all that is left of this messy and bloody modern China project is a nation-state with long dilapidated foundations. Its government’s legitimacy to rule still exclusively comes from saving and modernizing China from the threats of imperialism. China’s rabid nationalists still rationalize their behavior as a defense against the wrongs by European and Japanese aggressors perpetrated more a hundred years ago. Border disputes get placed into this context of national affront. Sure, all this reactionary energy had propelled China back onto the world stage, but we are well on our way into the 21st Century already. Are long-gone grudges really sufficient to justify the contours of China’s current nation-state, especially when China has historically been more than a nation-state?

And if the old imperial rulers of China had already figured out something bigger than nation-states, then why constrain what it means to be Chinese to a singular culture represented by cheap pagodas, dragons and scallion pancakes, when the various Chinese empires had already come to encompass a dazzling array of cultures and languages? Why restrict China within political borders to one geographic area on the globe, when China itself has morphed and shifted its shape over time? Why clench onto the notion of China to be nothing but one singular state under one government, when the ren of China has coexisted as the min of many states?

In China, from the dichotomy between ren and min, the Chinese ancestors had already figured out that nations and states need not be exclusively mapped to one another, and have conducted themselves accordingly. It’s time for China to be more than its nation-state Band-Aid. The people who had the foresight to know that people exist both as an end to themselves and as parts of a greater vision, the people who established multinational empires through coercion and violence but also through philosophy and trade, the people who brought to the world artistic, religious, and technological advancements, the people who hold themselves to be the heirs of one of the oldest civilizations on the planet, can be much more than a reactionary and defensive nation-state stuck in the past. Then maybe it wouldn’t have to constantly remind itself that its state really does belong to the renmin.

Edgar Degas’ The Rehearsal and Other Classroom Paintings

September 28, 2012 § Leave a comment

Edgar Degas’ The Rehearsal contains within its four corners almost every major theme that has ever been distilled from or assigned to the artist’s work on dancers. Four dancers are front center in the rehearsal room performing routine battement (a position in which one foot remains on the floor while the other is raised a little above the waistline). A group of dancers are situated behind them—one bent over, two gossiping with each other near a floor-to-ceiling window, one all alone at the barre, and one demurely clasping her hands as she regards her fellow dancers performing their exercises. A scene out of a dancer’s everyday life. There is in theory no mismatch between the common subject and loftier artistic platform, but one does exist as a matter of fact. And so, many have observed that Degas’ paintings of dancers ingeniously elevate the banal into the beautiful. The dancers rehearse in a room part gray, part brown, lit only by natural light from three floor-to-ceiling windows. Paint on the walls is old and peeling. Only one wall is equipped with a barre. Degas knew that the humble, urban condition of the studio was much more a part of the dancer’s craft and culture than the Palais Garnier where she performed. Hence the caption next to The Rehearsal at its home in The Fogg Museum of Art reads, “We see Degas’ concern with painting modern experiences, especially in urban settings.” And finally, we have word from Degas himself that he chose to paint dancers because he was fascinated by movement. Banality, urbanity, movement—all evident in The Rehearsal, but it seems less than satisfying to end the examination of the painting there, for these three can be found in almost any Impressionist painting. We would expect that Degas, with his unique subject and professed realism, brought something different to the table.

Ballet, relative to other art forms, was an anomaly in Degas’ time. When new artistic movements were gathering steam—impressionism, realism, and romanticism at the forefront of the parade of isms—French ballet remained a bastion of classicism. Precision, poise, technical proficiency. These were the objectives of a French dancer. The body never out of position, the classical line held both figuratively and literally, the limbs always in alignment with fingers, feet, and head. In spite of its near-regimental formality, the classical method had a sort of alchemy to it—a way in which strict adherence to technique transformed craft into art. Classical purity faithfully fulfilled that one requirement of good art that seemed so elusive—true understanding of the art form. Virtuosity meant connecting with and personifying the art’s essence, becoming its ideal. Coldly classical, and yet innately balletic.

But Degas operated in realism. There are hints of classical rigor here and there. A visible relic of a grid pattern and the fact that each dancer en battement is in exactly the same position indicates the use of studies and in-depth preparation before oil was applied to canvas. Indeed, Degas would often sketch drawings from life or photographs, transfer the images onto the canvas, and then modify them to comport with the work as a whole. In some cases, the last step was repeated several times as Degas scraped off parts of a painting and redid them, adding new characters or changing the setting. Meticulous craftsmanship is where the similarity with classicism stops, however, as Degas stuck to the realist credo of depicting life as it is without photographic accuracy. The lighting of the room is masterfully exact, the combination of dull palette and natural light from the windows providing the muted glamour of a ballet rehearsal. The dancers’ extremities are vague. Fingers are gnarled if at all visible. Faces of the dancers in the foreground are lightly sketched, but most have no face at all. Their limbs, the cradle of the arm where the elbow is slightly bent, the curve of the calf visible below the tutu, are delineated with special clarity. It is no accident that classical ballet also emphasizes these parts of the body. The one extremity that Degas has chosen to detail is the dancer’s foot, recognized by most as ballet’s trademark. The dancers en battement are given point shoes with little to no shadowing, indicating the foot is perfectly balanced within the shoe; the raised foot exhibits a perfect dancer’s point. Contrast that to the dancer at the barre, whose left foot is slightly leaning to the right while her leg stays straight, indicating imperfect balance. The slight curve of the shoe underneath the foot’s arch owes to the stiff shank supporting the dancer when she is en pointe. In the painting, the feet are as alive, if not more so, than the limbs.

To have observed his subject so closely as to notice and accurately paint these details was more than enough to uphold the realist’s burden. Degas goes further. He leaves the ballet instructor out of the painting. Not all dancers are performing the same exercise, and most are not even rehearsing at all. The impression is one of instinctive order, something unnamed that produces uniform positions and progress despite seeming lack of focus on the task at hand. For the mature dancers in the painting, this would have been a natural and essential byproduct of years of training. On the other hand, these dancers are not mere slaves in the corps. The sashes around their waists are different colors, as are the ribbons in their hair; some opt for flowers in their hair instead, or curls rather than a traditional bun. Degas has strived to ensure the uniqueness of each dancer amid the obsession with uniformity, and with a simple game of dress up, he has succeeded.

It is not a coincidence that the details Degas chose to include—those he deemed necessary for a realistic painting—are all core elements of French classical ballet. Concentration on the limbs and the body because the face only gets in the way. A corps made up of individual, distinct dancers who are recognized as such but move as one and do not draw attention to themselves. Discipline and muscle memory of position that can only be acquired through classical conditioning. Degas may not have shared the classicist’s devotion to unlocking essence through formal technique, but he has demonstrated virtuosity in realism through understanding the essence of his subject. Indeed, if The Rehearsal is more than a rendering of dancers in rehearsal, it is a meditation on the role of essence in classicism and realism, artistic movements on opposite ends of the spectrum. Granted, the two interact with essence in different ways—one seeks to find it within itself, the other seeks to paint its portrait. But they both ultimately speak in the language of essence; it guides them through their art, gives them an objective and a definition.

When The Rehearsal is examined in conjunction with Degas’ other classroom paintings, the connection he draws between classicism and realism becomes stronger and richer still. All situated in the foyer de jour at the Hôtel de Choiseul, where the ballet corps of the rue le Peletier Opéra held classes and rehearsed, the first of the classroom paintings is believed to have been completed a few months before a fire destroyed much of the building’s interior in 1873. The last paintings in the classroom group were perhaps begun before the fire but were completed after when Degas could only turn to his memory and sketches for reference. Given this constraint, a lack of complete pictorial accuracy in his portrayal of the dance classes would be understandable, even expected. What is puzzling is that the physical and artistic attributes of the classroom vary from painting to painting. If this were due to memory, the works would at least be consistent with one another, even if a consistent departure from the actual look of the classes Degas sketched. So if not memory, what other explanation can we turn to? Artistic purpose is a good candidate, and one can sense an almost mischievous one here as the paintings appear near-documentary at the same time that they are coy and noncommittal about the characteristics of their subject.

According to old floor plans and photographs, the foyer de jour measured thirty by twenty-five feet and had three floor-to-ceiling windows overlooking the Hôtel de Choiseuel courtyard, whose two large trees can be seen in The Rehearsal. In The Dance Rehearsal, the first of the classroom paintings, we learn that the interior of the room was divided width-wise by a row of heavy, wooden, round-sectioned columns and that at one side of the room, a dark stairwell surrounded by a handrail allowed access to the basement below. The lighting of the room is dark and muted, reminiscent of a winter day, due to the shadows from the columnade. In The Rehearsal, however, Degas opens the space up by taking away the columns and stairwell and adding warmer natural lighting. The floorboards of the two paintings run in opposite directions and their window jambs are of a different length. The best explanation for the discrepancies can perhaps be found in the fact that there were almost no discrepancies to speak of. Recent x-ray and infrared examinations show that The Dance Rehearsal’s columns and stairway were originally included in The Rehearsal, only to be scraped out later by Degas. This did not mean that Degas believed the open space to be a better representation of the foyer, for the columns and dank lighting appear again in a later painting entitled Dancers Practicing in the Foyer. The final classroom paintings, however, follow The Rehearsal’s uncluttered setting and increase the brightness of its already serene, summery lighting. No photographs of the foyer can confirm either depiction as the more accurate one, nor would we want them to lest we be able to identify Degas’ transformation of reality in only a subset of classroom paintings.

For in the end, the real fun of Degas’ classroom paintings is their proposition that we do not even need truth to have realism. We have no idea which of the foyers captures the characteristic of the actual foyer de jour, but we know that at least one of them, if not both, do not. And yet, we do not have any less faith in the realism of these paintings: they still give the impression of artistically rendered photographs, truly and accurately showing a moment from a dance class. Part of this faith comes from Degas’ grasp of and ability to render the essence of his subject. It also comes from Degas’ ingenious and cheeky insight that realism does not mean lack of artifice. It does not matter that the artist has taken great liberties with his subjects as long as they appear familiar enough to be recognizable. The illusion works precisely because of something classicism first discovered—that art is meant to be artifice. It is a game of suspension of disbelief, one which well-executed art will always win. Realist and classicist methods are not quite symmetric, though, in this area. Classicist art operates by its own rules, creating an entirely different world that is appreciated as such; if any relevance to our own world is established, it is done by our affirmative efforts. Much like their use of the concept of essence, classicism and realism take the fundamental building block of artifice and apply it to promote their own goals—one deceives plainly, the other more stealthily. How unexpected and eye-opening that scenes so mundane could be responsible for highlighting these intersections. For a realist artist painting classical artists at work, the connections could not have been more perfectly made.

Some Closure on Jiang Zemin (Not That Kind): A Party Elder’s Death by Twitter

July 12, 2011 § Leave a comment

By Rebecca Liao

As celebrations got under way in The Great Hall of the People for the 90th anniversary of the Chinese Communist Party, CCTV gave each party elder their customary close-up–except for the elder who loved close-ups most of all. A wide-angle shot of the tableau revealed that former President Jiang Zemin was indeed absent. Since retiring in 2003, Jiang had been at every official event, eager to remind the party and the public of his still-formidable authority as Retired Party Elder #1. Immediately, speculation ran rampant about the reasons for Jiang’s absence: he was making a political statement; he was ailing from a massive heart attack suffered in April earlier this year; the party was confirming his diminishing influence as China prepares for a leadership transition next year. Netizens, however, betting that the rules of the modern Chinese workplace applied within the party as well, came up with the only reasonable explanation: he was dead. And so ensued a tense, “Is he or isn’t he?” that became more and more comical with each piece of information offered, whether it was through news organizations, Sina Weibo, or Twitter. Relive the cat-and-mouse action through my Tweet-tracker, which was programmed to rescue any nugget that would have been deleted or blocked (or was deleted or blocked) by Chinese government and Sina Weibo censors. Read the rest of the story here!

Thoughts on “Beginning of the Great Revival”

July 5, 2011 § 3 Comments

By Rebecca Liao

To celebrate July 4th this year, I saw Beginning of the Great Revival (or The Founding of a Party in the People’s Republic of China), a movie released last month by the Chinese government to commemorate the 90th anniversary of the Chinese Communist Party. While the film does not have anywhere near the level of propaganda in films from the Cultural Revolution, it would be hard to miss how badly the government wants people to buy into this movie. The state’s initiatives have a strange resemblance to the New Yorker’s offering Jonathan Franzen’s piece about David Foster Wallace to readers for free as long as they “liked” the magazine’s Facebook page. Only, Beginning of the Great Revival is not as seamless as Franzen in its presentation of a very complicated narrative. And even if people had read Franzen’s piece primarily to keep abreast of a Very Important Writer, the compulsion cannot be compared to being deprived Transformers: Dark of the Moon and Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows: Part 2 (on the big screen, that is: the former is already available on the streets in China and the latter will be available soon) until Beginning of the Great Revival grosses in the nine figures domestically. My seeing the movie in the U.S. was not going to help my people back home. But to indulge in a healthy dose of American irony with a side of Chairman Mao’s favorite raw, hot peppers, I ambled into the nearest AMC theater and took my place between an elderly Chinese woman who kept an excited running commentary and a little boy who really only showed interest during the assassination scenes. Here are my 8 lucky thoughts about the movie:

1) Seeing stars. Nearly all the A-list actors and actresses in China make appearances. Chow Yun-Fat as the delusional emperor Yuan Shikai, Liu Ye as Mao Zedong, Zhou Xun (Zhang Ziyi’s rival before Zhang decided dating billionaires was such a better business strategy) as Wang Huiwu, Andy Lau as Cai E, Fan Bing Bing as the Empress Dowager Longyu, and on and on. Coupled with the breadth of historical events covered and the expansive mise-en-scene, the spectacle was breathtaking and relentless, much like the opening ceremony of the Beijing Olympics. When it comes to mobilizing large numbers of talented people, China is second to none. Most of the actors and actresses waived their fees to be a part of this film. I hate to beat the we’re-losing-to-China dead horse, but can you imagine Brangelina or any American A-lister doing the same barring a highly-publicized natural disaster?

2) It’s weird to think of Mao as a human being. Chairman Mao as a passionate, earnest and capable leader is a time-honored (and probably pretty accurate) persona. Mao as a romance hero? Several Mao-glorifying scenes earned a smirk, but the subplot about his romance with his second wife, Yang Kaihui, whom he abandoned in real life to shack up with a 17-year old, was just cringe-worthy. She is charmed by his height and intelligence, he by her innocent, playful nature. On his deathbed, her father and Mao’s favorite teacher, Yang Changji, wakes from a coma and gathers enough strength to clasp the lovers’ hands together. This is just way too much cheese for a lactose-intolerant population.

3) Chinese history is complicated. Beginning of the Great Revival tries to cover the events from the Xinhai

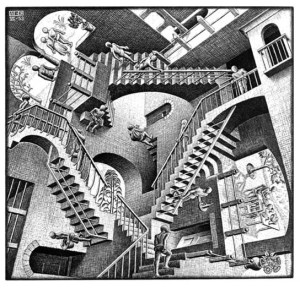

M.C. Escher’s Relativity (Source: http://evansheline.com)

Revolution in 1911 to the founding of the CCP in 1921 in just over two hours. Because the film is an officially sanctioned version of history, omitting any historical figure would fuel speculation about who is out of favor with the Party and what that means for the Party line. Labels that pop up as each person is introduced help, but the sheer number of players and the complexity of their political relations is still a challenge. Superficial treatment of most significant events was necessary but certainly increased the confusion. There’s nothing quite like this period in Chinese history. However, I imagine that if we condensed War and Peace into 200 pages without eliminating any characters and mapped them onto an M.C. Escher lithograph littered with land mines, we’d have something comparable.

The number between 3 and 5) Hots for the teacher. The Chinese lionize their scholars. On film (and in real life, to a certain extent), they are categorically hot. They are brilliant, charismatic, dignified, and passionate, with rhetorical gifts that produce witty repartee one moment and rousing revolutionary speeches the next. They’re also good looking. That’s all.5) Speaking of beating a dead horse. When will the story of foreign aggression grow stale? This is not at all meant to be a point of criticism: a depiction of the events leading up to the May 4th Movement must include the humiliation of having Germany transfer Qingdao and Jiaozhou Bay to Japan as part of the Treaty of Versailles. But to this day, foreign encroachment on Chinese sovereignty and general disrespect on the international stage are the sorest spots in the Chinese psyche. No doubt they have been a great source of motivation to develop the country as quickly as possible, but now they serve mostly as demagogical levers for the government. China has essentially become a capitalist country. As is the case for every successful startup, the narrative has to go from, “We have come so far,” to, “Where are we going next?” High-speed railways, longest bridges in the world, the lone spot of economic stability as the rest of the world founders—these have been on every pundit’s list of talking points in the past year. China has captured the world’s imagination; how does it grow its soft power? First thing’s first: step out of the shadow of rapid ascension and embrace sustained change and growth.

6) Speaking of soft power. AMC Theaters inked a deal with China Lion Film Distribution to exclusively distribute the film in North America. In the U.S., it is showing in 29 theaters, all in the Chinese immigrant hotbeds of New York, Los Angeles and San Francisco. While this movie will never be an Oscar contender, it is interesting to see how it stacks up against the box office performances of the last five Academy Award winners for Best Foreign Language Film, the most recent three of which enjoyed the press of the win and two of which received positive critical attention in major domestic publications when first released. On average, they grossed $115,394 in their opening weekends and had a ranking of 39, but were only shown in eight theaters. By contrast, Beginning of the Great Revival grossed $65,866 in its opening weekend and ranked 37th, but is playing in 29 theaters. There is a certain appeal to the regular art house film crowd of a stylishly filmed propaganda movie, but let’s be honest: AMC was betting that blood would be thicker than water. We’ll have to wait until the end of the movie’s run for a final verdict, but it looks like the Chinese are actually quite good arbiters of quality.

7) Do not try this at home. The irony of a government-sanctioned film commemorating a revolutionary response to injustice and oppression was not lost on the mainland Chinese audience. If anything, though, the irony serves more as a reminder of the government’s power than as motivation for demanding reform. Still, the first step towards legitimizing a social movement is to glamorize it: the government should be careful what it wishes for.

To get you in the mood for number 8:

8) The East is Red. In a desperate attempt to regain political clout ahead of China’s imminent leadership transition, “Chinese JFK” Bo Xilai instituted a campaign to revive Red culture in Chongqing, where he is mayor. The charm offensive directed at Beijing includes sing-a-longs to Red songs, Red song singing competitions, and readings of Mao’s poetry.

Surprisingly, not everyone is laughing. It turns out there is significant nostalgia for the days of Chairman Mao, not because anyone longs for famines or the Cultural Revolution, but because there is something about Red culture that the Chinese feel proud to claim as part of their DNA. The revolutionary impulses in the film that the government is trying to promote and suppress at the same time have free expression in Red songs. This is true for many people in mainland China, but all the more so for the workers and peasants that are the songs’ heroes. Chairman Mao rose to power off of the widespread anger and fatigue of the working class—perhaps his rehabilitation is not so much an exhortation for the newly wealthy Chinese to remember his ideas as it is a reminder that his ideas have not been forgotten by the CCP. Altogether, now:

“On China,” by Henry Kissinger

May 22, 2011 § 1 Comment

By Rebecca Liao

As expected, Kissinger ends his relative quiet on a major foreign policy issue with a treatise. Taking bets now that Christopher Hitchens will be ready with a scathing review in Slate, or even Vanity Fair, by the end of the week.

The Chinese have a very dark sense of humor

May 2, 2011 § 2 Comments

By Rebecca Liao

In response to the death of Osama bin Laden, the following parable went viral on the web in China:

Al Qaeda once sent five terrorists to China: One was sent to blow up a bus, but he wasn’t able to squeeze onto it; one was sent to blow up a supermarket, but the bomb was stolen from his basket; one was sent to blow up a train, but tickets were sold-out; finally, one succeeded in bombing a coal mine, and hundreds of workers died. He returned to Al Qaeda’s headquarters to await the headlines about his success, but it was never reported by the Chinese press. Al Qaeda executed him for lying.

Read more from Evan Osnos here.