Grading President Ma Ying-Jeou

May 2, 2013 § Leave a comment

“Taiwan is a responsible stakeholder and a peacemaker in East Asia. Taiwan’s democratic experience is a model for China, and we have long been a friend and ally of the United States…”

President Ma Ying-jeou had just concluded his remarks over videoconference amidst applause from the audience at Stanford University. Former Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice, the moderator of the evening’s proceedings, thanked the president and the participants.

Behind the lectern where Ma spoke earlier—most likely a room in the Presidential Office—the seal of that office hung above the words “Republic of China (Taiwan).”

* * *

People unfamiliar with Taiwan probably have good reason to hold President Ma Ying-jeou in high esteem. As Ma mentioned in his speech, which he delivered in his usual, mellow Confucian-scholarly style: “There were two flashpoints in East Asia, and while the world is focused on one of them right now, the other one has disappeared.” He is referring to, of course, the Korean Peninsula and the Taiwan Strait. Looking at the Taiwan Strait, over the very same waters into which ballistic missiles were fired as recently as 1996, more than 600 direct commercial flights now fly weekly, shuttling investors, tourists and exchange students. China has gone from Taiwan’s largest military threat to Taiwan’s largest trading partner, surpassing the United States and Japan in 2005 as well as becoming the only country to conclude a bilateral trade liberalization framework agreement with Taiwan. The people on both sides never dreamed of possibly exchanging postcards one day; today, pro-independence leaders in Taiwan have their own social media accounts in China (which were rather swiftly banned, but no victory is too small). Not a few magazine articles in the U.S. painted Ma Ying-jeou and his administration as one of the most important and creative peacemakers in the 21st century.

If this were true, I for one certainly welcome this brand image for Taiwan. Shut out of most major international organizations, including those under the United Nations, the Taiwanese people have long thought of ways to make themselves visible and recognized by the world. Imagine down the road—a Taiwanese leader receiving the Nobel Peace Prize for successfully defusing tensions between Japan, the United States, and China over oil rights in the Western Pacific by engaging the leaders in a series of four-way dialogues. Maybe Taiwan and China could come to a permanent peace accord that secures the independence of Taiwan’s way of life and China’s sense of national unity. Or Taiwan acting as the unofficial ombudsperson of East Asia, mediating conflicts stretching from Russia in the north, to New Zealand in the south. At Taiwan’s suggestion, Asian economies cooperate to build new standards in finance, capitalism and social order, based on ancient Asian principles of mutual respect. On that day, people will be proud to be called Taiwanese.

But let’s come back down to earth for a bit. This fantasy would no doubt be great for Taiwan. Is it, however, just a fantasy? Is Ma Ying-jeou a real visionary, or is he living in his own naïve la-la-land?

For one thing, when Prof. Rice asked Ma whether growing closer to Taiwan is a positive move for the U.S., Ma stressed that Taiwan-U.S. relations improve whenever he reduces tensions between Taiwan and China. This understanding of the US-China-Taiwan balancing act is rather juvenile. Indeed, in the years prior to 2008, tensions between Taiwan and China were at a high point, causing alarm for the United States. The U.S. did not want war to break out, as it would likely need to jump into the conflict to retain its position and allies in the area. Chen Shui-bian, president at the time and member of the pro-independence party in Taiwan, was chastised by the Americans for acting like a kid who kept poking the tiger just to see what’ll happen. Therefore, it is understandable that the U.S. would like tensions to subside—which Ma pretty much accomplished simply by getting elected, since his pro-China party would by no means be any more provocative.

Any further warming of relations between Taiwan and China, I believe, should be evaluated case by case where American interests are concerned. Favored trade treatment, or high level joint military meetings, is certainly tying the two sides closer; but as the U.S. is ramping up competition with China over trade and security concerns, Ma’s policies may very well bring sparks of uncertainty to American objectives in East Asia. Furthermore, after five years of the détente of “easy topics first,” China is running out of patience for Ma to get talking on the harder topics of political and regulatory integration. The pace of Taiwan-China honeymooning has already alarmed some in the States to the point of advocating for simply dropping support for Taiwan. The more politically and militarily integrated Taiwan is with China, the harder it is to keep asking America to see Taiwan as simply a friend and an ally.

Likewise, portraying Ma to be the peacemaker across the Taiwan Strait might just be giving him too much credit. The series of changes in China policy by Ma’s administration, such as opening up direct flights, allowing for exchange students and tourists, etc., could at best be described as a reversion to the mean—any two non-hostile states would have all of those things as well. They are not exactly “improving” relations, so much as “repairing” relations, which in reality had already begun under the previous DPP administration. In other words, they have picked the low-hanging diplomatic fruit. As I mentioned above, Ma’s real test is just coming around the corner, when he has to balance dealing with deeper integration with China on the one hand, and being on the American side of the Western Pacific power partition on the other.

More importantly, standing in the city alleyways or the edges of rice fields in Taiwan, Ma and the KMT’s policies of economic liberalization feel more like the product of short-sighted, profit-driven capitalists in fear of being left out of the China gold rush. Yes, many Taiwanese small businesses are better off today thanks to Ma’s policies. But the vast majority of the value created by cross-straits liberalization has been gobbled up by a small group of large corporate interests and their investors. Many large, profitable Taiwanese companies like Foxconn are built on exploiting the draconian labor conditions in China. Taiwanese real estate prices have skyrocketed in a bubble caused by Chinese speculators with the government abusing eminent domain powers to steamroll over old neighborhoods at the request of developers. The administration has been dumbfounded about whether pro-China interests can freely buy up news media. To the Taiwanese, opening up with China has not brought the economic paradise that Ma’s administration promised. Instead, it gave birth to a vicious profit-mongering snake, exacerbating the wealth inequality in both societies. President Ma is either too naïve to see that these are the results of his well-intentioned neoliberal economic policies, or he is knowingly working as a faithful servant to this predatory monster.

On screen, President Ma Ying-jeou looked so proud of his accomplishments, like a third grade student of the month taking photos with the principal. But does he know that the principal has already started to have doubts about him, that he might have gone overboard with his assignment to calm the paranoia in the Taiwan Strait? Maybe he does know. Forging an accord for fishing rights near the Diaoyutai/Senkaku islands with Japan might be a subtle shift towards the U.S.-Japan sphere of power; at least Beijing for sure is not going to congratulate Ma anytime soon for “settling sacred Chinese territory” with the enemy. The so-called “agreement” signed by a rebellious provincial leader is not enforceable, obviously.

Going forward, I support wholeheartedly the principle of finding common pragmatic values, and I support the vision where the world looks to Taiwan as a wise, mature advocate of peace, not just between states but within our interconnected societies as well. President Ma Ying-jeou has helped to reduce the probability of imminent war between Taiwan and China. But in that process, he has set Taiwan on a course towards uncharted waters—continued integration with China that will pull Taiwan out of American interests and unleash unforeseen catastrophes onTaiwanese society. Can President Ma or his successor leaders steer Taiwan through these torpedo-laced channels? Best of luck to them.

Taiwan Should Abolish the DPP and the KMT

May 2, 2013 § Leave a comment

Committee meetings in Taiwan’s Legislative Yuan are usually held in small conference rooms at the parliamentary courtyard, a cluster of old buildings that used to house a girl’s high school when the Japanese ran the show. On a hot afternoon in 2006, approving a big purchase of weapons from the United States was on the agenda.

Out of the blue, the right honorable member of parliament Li Ao walked to the lectern and began spraying tear gas into the air, disrupting the proceedings. Pandemonium broke out as the room filled with noxious fumes, and the highest representatives of the people scrambled for fresh air. This incident stands along the many other fistfights, shouting matches, and other such closing acts of Taiwan’s biggest circus, its legislature.

People who are not from Taiwan often marvel at its so-called “democratic miracle”—that is, how can such a friendly, hospitable people elect the goofiest and most immature political leaders? Similarly, the people of Taiwan ask themselves, where did things go wrong?

To correctly diagnose the problem, one must understand that Taiwan’s democratization story is part of a much larger one. It can only be completely understood along with Taiwan’s story of “independence versus unification,” or more precisely, the question of Taiwan’s national identity. As a result of Taiwan’s turbulent history, two competing national identities coexist in Taiwan. Democratization was a strategy that allowed both sides of the national identity conflict to wage war in a more civilized, air-conditioned setting, inside the halls of politicians and off the streets of protestors. Therefore, to induce Taiwan’s democratic governance to be more efficient (both in representing the myriad of societal wishes and in delivering on administrative promises), we must look at the problems brought on by the national identity conflict side of the equation.

A quick overview of the conflicting national identities in Taiwan can never give enough justice to the centuries of history they represent, but it is roughly as follows. On the one hand, some identify with a Taiwanese ethnic nation. It can be traced back as early as Taiwanese elites’ calls for higher degrees of self-rule within the Japanese colonial empire in the 1920s, which stemmed from their identifying themselves as a different entity from both the people on the Chinese and Japanese homelands. Later, a bloody and tragic clash of Taiwanese locals and the new rulers from China in 1947, and the social pressure of having to absorb an entire refugee society after 1949, added to the urgency of a strong Taiwanese state. The transplanted Chiang Kai-shek military one-party government did themselves no favors by crushing any bud of dissent. All these experiences produced a defensive identity for a nation that, at its purest form, is a people deserving of its own state under the 20th century classic notion of self-determination.

On the other hand is a national identity, identifying with a republican, unified China encompassing all that could possibly said to be Chinese, realizing the dream of 19th century reformers and revolutionaries led by Dr. Sun Yat-sen. The dream went into full force as democratic revolution became the solution to imperial China’s corruption, backwardness and powerlessness against modern Western colonialists. After a long series of crushing blows to the project by ambitious strongmen, warlords, carpetbaggers and incompetent officials, the republic endured almost a decade of desecration by the Japanese but finally surrendered power to the Communist Party. The years of war scorched much of the land, and those who fled the mainland to Taiwan were separated from their families and roots, in many cases permanently. The democratic China project lies at the bottom of this well of history, tarnished and unfinished.

In Taiwan, the responsibilities of achieving these two conflicting national identities have fallen on the two major political parties, the Chinese Nationalist Party (the KMT) for “Republican Greater China” and the Democratic Progressive Party (the DPP) for “Self-Determined Ethnic Taiwan.” Of course, the two nation-building projects have long predated the formation of either political party. But as the nation-builders organized, they realized that for them, nation-building necessarily meant state-building as well—taking over the power of sanctioned authority. This was the case for the KMT in the 1920s when the first Chinese republican experiment failed at the hands of Yuan Shikai; it was also the case for the DPP in the 1980s when they were formed to oust the authoritarian KMT government. In other words, both the KMT and the DPP are less governing political parties and more revolutionary nation-building organizations at heart.

And herein lies the problem with Taiwan’s democracy: two nation-building projects are vying for control over the same state apparatus. Between 1945 to 1987, the Republic of China government in Taiwan was a one-party martial law state controlled by the KMT. It continued its nation-building project in Taiwan, forcing on the populace an identity that did not match that of the majority of its citizens. This further consolidated the nativist Taiwanese self-determination cause, which contributed greatly to the anti-government and pro-democracy sentiment. In the 1980s and 90s, mass anti-government protests led the KMT to allow the opposition to enter national elections—the two sides chose democratic competition and compromise as the dueling ground, rather than violent revolution. The result for the previously seditious independent Taiwan project is that while now legitimatized, it had conceded the opportunity to eradicate and outlaw the republican Greater China project. The two camps therefore agreed to continue the fight in the parliament and through election campaigns.

This arrangement certainly produced an immense benefit for Taiwan’s society; that is, the costs of all-out military revolution had been avoided. But throughout the next few decades, this arrangement created structural strains, both on the actual need for Taiwan’s society to consolidate a workable identity inclusive for all its members, and for the daily functioning of Taiwan’s governing institutions. On the front of consolidating a workable identity, the current situation allows top-down nation-building along outdated and contradictory models to persist and encumbers transitional justice for the victims of martial law under Chiang Kai-shek. As for improved functioning of Taiwan’s governing institutions, the current situation burdens pragmatic considerations in Taiwan-China relations and immobilizes the political process’s ability to deal with pressing domestic issues such as development, distributive justice, and social welfare.

So here is a modest proposal to Taiwan’s civil society: abolish the KMT and the DPP, and rebuild a spread of political parties along ideological and issue boundaries. Let there be labor parties, environmental parties, parties representing free market capitalism and parties representing social democracy. Let the people who agree on how governance and the governed should interact from the KMT and the DPP get together and work towards their goal. Let the spectrum of political parties reflect the spectrum of issues and wishes of the voters.

Okay, maybe that’s a bit of a stretch. The KMT and the DPP are probably here to stay. It would be hard to imagine a social force great enough to pressure both parties into committing political suicide and giving up its infrastructure and core supporters. The national identity question will still remain and seep back into politics. Fortunately, both the KMT and the DPP understand that the political tectonic plates are indeed shifting. Student movements of recent years have sprung up in response to the mistreatment of old factory workers, violent removal of residents for urban renewal projects, monopolization of news media, and nuclear energy policy. Beijing has been pushing for more complex, intertwined regulatory, trade and legal modes of interaction beneficial to its side. All of these issues demand both parties commit to a clear stance, and more importantly, to a clear ideology so people will know what to expect in the future. The two parties will not have to merely adjust their policies, but think hard about their legacies and organizational power structure as well.

There is a lot of soul searching in the horizon for Taiwan’s two major parties. A lot of work still needs to be done if the people of Taiwan want to replace politicians weaned on nationalistic fervor with those that are pragmatic in their approach and empathetic in their service to the people. Perhaps then we will see Taiwan’s parliament as less of a circus and more of a proper, respected arena where a small committee meeting might just produce a small glimmer of optimism.

We the People’s Republic of China

January 24, 2013 § Leave a comment

Some years ago, it seemed like every tourist visiting China was on the lookout for the same souvenir: the canvas bag emblazoned with the words wei renmin fuwu, “Serve the People,” in none other than Chairman Mao’s own handwriting. Was it the nonconformist symbolism of the Chinese Communist propaganda style that caught the foreigners’ eyes? Or was it the historical significance of Chairman Mao’s words that resonated? Who knows, and no one really cares. Not to the Chinese, anyway, as long as money is to be made.

Except the Chinese do care about what the word renmin means. There is China’s formal name, Zhonghua Renmin Gongheguo (中華人民共和國, “The People’s Republic of China”); Renmin Univeristy (人民大學); China’s legislative venue the Renmin Dahuitang (人民大會堂, “The Great Hall of the People”); China’s high court the Zuigao Renmin Fayuan (最高人民法院, “The Supreme People’s Court”), and on and on. Renmin translates into “people,” here used liberally to denote the members of the classless society established after the proletariat revolution, as if the people need some sort of constant reminder that the government belongs to them (nominally, anyway). Point being, the concept of the renmin goes back deep into the origins of China.

Renmin is made up of two more basic parts, ren and min. Just to confuse our non-Chinese readers, ren, min, and renmin can all be translated as “people.” Good people, bad people, tall people, short people, French people, indigenous people, etc. However, the connotations between ren and min are distinct. Ren denotes individual persons, describing a person as just him or herself, closer to the concept of a “human being” in English. A good person is a haoren; a benefactor is a guiren, a beauty is a meiren, and so forth. Hanren, is the Han ethnicity. Zangren, Tibetans. Ribenren, Japanese. Min, on the other hand, refers to a group of people under political rule. The Chinese word zimin literally means a prince’s people, or the English word “subject”; nanmin means people in crisis, or “refugee”; gongmin means people in public, or “citizen.” The people denoted by min is more like “We the People” with the capital P.

Perhaps, then, we can say, the Chinese language differentiates between “people” as simply a group of persons with distinct identities and characteristics, and “people” as one collective body subject to a common political fate. In other words, the people comprising a “nation” and the people under a “state.”

This offers some clues as to how China thinks of herself as a nation, a state, and a nation-state. The Chinese usually like to think of themselves as one nation and one state since the beginning of time. When a Chinese person talks about his heritage, it’s not uncommon to mention China’s “5,000 year history” and all Chinese being “heirs of the dragon.” However, beginning with the Qin Dynasty and much more so in the Han Dynasty in 206 BC, China was already an empire encompassing all sorts of ren—a variety of nations under one state. The state came first through war and continued to preside over a mixture of ethnicities and tribal clans.

To rule over all these different ren, the state must turn them into min. The Han rulers established a system of imperial examinations, through which social advancement was based on mastery of Confucian thought. This effectively established one philosophical and political system of thought for the entire populace, not just by brute cultural assimilation (though there was certainly no shortage of that) but, more importantly, by political indoctrination. Throughout China’s history, the imperial examination system had been one hallmark of all of the dynasties that ruled China. This includes the proud cosmopolitan dynasties like the Tang, the Song and the Ming (partially anyway), but also the non-ethnic-Han dynasties of the Yuan and the Qing. We may not be sure whether the people living in southeastern coastal areas felt a cultural connection with those living near the northern deserts, but they were all hoping to secure a seat in government and a mansion in the capital by taking the test. In this way, the succession of empires in China conducted nation-building within their borders, but I would argue that up until the end of the Qing in 1911, China was not a nation-state. It was much bigger than a nation-state.

Certainly, during the turn of the 20th Century, when ancient Asian empires clashed with modern European nation-states, China had to avoid the fates suffered by the Ottoman Empire (which shattered into many pieces) and India (which became a colony under a European power). Through violent revolutions, China guzzled up Western ideologies and tried to masquerade itself as a singular nation-state. Sun Yat-sen himself envisioned a purely ethnic Han nation-state in the beginning and only later acquiesced to “Hans, Manchus, Mongols, Uighurs and Tibetans” as part of the “Chinese nation.” Thus, in an utterly hasty fashion, a new nation-building and a new state-building project began in the ruins of the old Qing Empire. The process was anything but civilized (just ask the Tibetans), but the means justified the ultimate end: to create an united front in order to vindicate the humiliation suffered at the hands of 19th Century imperialists.

In 2013, after every Western ideology has run its course in China, all that is left of this messy and bloody modern China project is a nation-state with long dilapidated foundations. Its government’s legitimacy to rule still exclusively comes from saving and modernizing China from the threats of imperialism. China’s rabid nationalists still rationalize their behavior as a defense against the wrongs by European and Japanese aggressors perpetrated more a hundred years ago. Border disputes get placed into this context of national affront. Sure, all this reactionary energy had propelled China back onto the world stage, but we are well on our way into the 21st Century already. Are long-gone grudges really sufficient to justify the contours of China’s current nation-state, especially when China has historically been more than a nation-state?

And if the old imperial rulers of China had already figured out something bigger than nation-states, then why constrain what it means to be Chinese to a singular culture represented by cheap pagodas, dragons and scallion pancakes, when the various Chinese empires had already come to encompass a dazzling array of cultures and languages? Why restrict China within political borders to one geographic area on the globe, when China itself has morphed and shifted its shape over time? Why clench onto the notion of China to be nothing but one singular state under one government, when the ren of China has coexisted as the min of many states?

In China, from the dichotomy between ren and min, the Chinese ancestors had already figured out that nations and states need not be exclusively mapped to one another, and have conducted themselves accordingly. It’s time for China to be more than its nation-state Band-Aid. The people who had the foresight to know that people exist both as an end to themselves and as parts of a greater vision, the people who established multinational empires through coercion and violence but also through philosophy and trade, the people who brought to the world artistic, religious, and technological advancements, the people who hold themselves to be the heirs of one of the oldest civilizations on the planet, can be much more than a reactionary and defensive nation-state stuck in the past. Then maybe it wouldn’t have to constantly remind itself that its state really does belong to the renmin.

Some Closure on Jiang Zemin (Not That Kind): A Party Elder’s Death by Twitter

July 12, 2011 § Leave a comment

By Rebecca Liao

As celebrations got under way in The Great Hall of the People for the 90th anniversary of the Chinese Communist Party, CCTV gave each party elder their customary close-up–except for the elder who loved close-ups most of all. A wide-angle shot of the tableau revealed that former President Jiang Zemin was indeed absent. Since retiring in 2003, Jiang had been at every official event, eager to remind the party and the public of his still-formidable authority as Retired Party Elder #1. Immediately, speculation ran rampant about the reasons for Jiang’s absence: he was making a political statement; he was ailing from a massive heart attack suffered in April earlier this year; the party was confirming his diminishing influence as China prepares for a leadership transition next year. Netizens, however, betting that the rules of the modern Chinese workplace applied within the party as well, came up with the only reasonable explanation: he was dead. And so ensued a tense, “Is he or isn’t he?” that became more and more comical with each piece of information offered, whether it was through news organizations, Sina Weibo, or Twitter. Relive the cat-and-mouse action through my Tweet-tracker, which was programmed to rescue any nugget that would have been deleted or blocked (or was deleted or blocked) by Chinese government and Sina Weibo censors. Read the rest of the story here!

Thoughts on “Beginning of the Great Revival”

July 5, 2011 § 3 Comments

By Rebecca Liao

To celebrate July 4th this year, I saw Beginning of the Great Revival (or The Founding of a Party in the People’s Republic of China), a movie released last month by the Chinese government to commemorate the 90th anniversary of the Chinese Communist Party. While the film does not have anywhere near the level of propaganda in films from the Cultural Revolution, it would be hard to miss how badly the government wants people to buy into this movie. The state’s initiatives have a strange resemblance to the New Yorker’s offering Jonathan Franzen’s piece about David Foster Wallace to readers for free as long as they “liked” the magazine’s Facebook page. Only, Beginning of the Great Revival is not as seamless as Franzen in its presentation of a very complicated narrative. And even if people had read Franzen’s piece primarily to keep abreast of a Very Important Writer, the compulsion cannot be compared to being deprived Transformers: Dark of the Moon and Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows: Part 2 (on the big screen, that is: the former is already available on the streets in China and the latter will be available soon) until Beginning of the Great Revival grosses in the nine figures domestically. My seeing the movie in the U.S. was not going to help my people back home. But to indulge in a healthy dose of American irony with a side of Chairman Mao’s favorite raw, hot peppers, I ambled into the nearest AMC theater and took my place between an elderly Chinese woman who kept an excited running commentary and a little boy who really only showed interest during the assassination scenes. Here are my 8 lucky thoughts about the movie:

1) Seeing stars. Nearly all the A-list actors and actresses in China make appearances. Chow Yun-Fat as the delusional emperor Yuan Shikai, Liu Ye as Mao Zedong, Zhou Xun (Zhang Ziyi’s rival before Zhang decided dating billionaires was such a better business strategy) as Wang Huiwu, Andy Lau as Cai E, Fan Bing Bing as the Empress Dowager Longyu, and on and on. Coupled with the breadth of historical events covered and the expansive mise-en-scene, the spectacle was breathtaking and relentless, much like the opening ceremony of the Beijing Olympics. When it comes to mobilizing large numbers of talented people, China is second to none. Most of the actors and actresses waived their fees to be a part of this film. I hate to beat the we’re-losing-to-China dead horse, but can you imagine Brangelina or any American A-lister doing the same barring a highly-publicized natural disaster?

2) It’s weird to think of Mao as a human being. Chairman Mao as a passionate, earnest and capable leader is a time-honored (and probably pretty accurate) persona. Mao as a romance hero? Several Mao-glorifying scenes earned a smirk, but the subplot about his romance with his second wife, Yang Kaihui, whom he abandoned in real life to shack up with a 17-year old, was just cringe-worthy. She is charmed by his height and intelligence, he by her innocent, playful nature. On his deathbed, her father and Mao’s favorite teacher, Yang Changji, wakes from a coma and gathers enough strength to clasp the lovers’ hands together. This is just way too much cheese for a lactose-intolerant population.

3) Chinese history is complicated. Beginning of the Great Revival tries to cover the events from the Xinhai

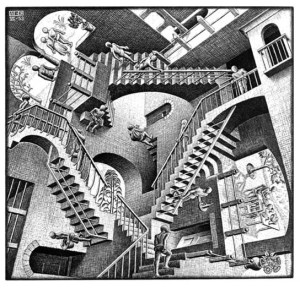

M.C. Escher’s Relativity (Source: http://evansheline.com)

Revolution in 1911 to the founding of the CCP in 1921 in just over two hours. Because the film is an officially sanctioned version of history, omitting any historical figure would fuel speculation about who is out of favor with the Party and what that means for the Party line. Labels that pop up as each person is introduced help, but the sheer number of players and the complexity of their political relations is still a challenge. Superficial treatment of most significant events was necessary but certainly increased the confusion. There’s nothing quite like this period in Chinese history. However, I imagine that if we condensed War and Peace into 200 pages without eliminating any characters and mapped them onto an M.C. Escher lithograph littered with land mines, we’d have something comparable.

The number between 3 and 5) Hots for the teacher. The Chinese lionize their scholars. On film (and in real life, to a certain extent), they are categorically hot. They are brilliant, charismatic, dignified, and passionate, with rhetorical gifts that produce witty repartee one moment and rousing revolutionary speeches the next. They’re also good looking. That’s all.5) Speaking of beating a dead horse. When will the story of foreign aggression grow stale? This is not at all meant to be a point of criticism: a depiction of the events leading up to the May 4th Movement must include the humiliation of having Germany transfer Qingdao and Jiaozhou Bay to Japan as part of the Treaty of Versailles. But to this day, foreign encroachment on Chinese sovereignty and general disrespect on the international stage are the sorest spots in the Chinese psyche. No doubt they have been a great source of motivation to develop the country as quickly as possible, but now they serve mostly as demagogical levers for the government. China has essentially become a capitalist country. As is the case for every successful startup, the narrative has to go from, “We have come so far,” to, “Where are we going next?” High-speed railways, longest bridges in the world, the lone spot of economic stability as the rest of the world founders—these have been on every pundit’s list of talking points in the past year. China has captured the world’s imagination; how does it grow its soft power? First thing’s first: step out of the shadow of rapid ascension and embrace sustained change and growth.

6) Speaking of soft power. AMC Theaters inked a deal with China Lion Film Distribution to exclusively distribute the film in North America. In the U.S., it is showing in 29 theaters, all in the Chinese immigrant hotbeds of New York, Los Angeles and San Francisco. While this movie will never be an Oscar contender, it is interesting to see how it stacks up against the box office performances of the last five Academy Award winners for Best Foreign Language Film, the most recent three of which enjoyed the press of the win and two of which received positive critical attention in major domestic publications when first released. On average, they grossed $115,394 in their opening weekends and had a ranking of 39, but were only shown in eight theaters. By contrast, Beginning of the Great Revival grossed $65,866 in its opening weekend and ranked 37th, but is playing in 29 theaters. There is a certain appeal to the regular art house film crowd of a stylishly filmed propaganda movie, but let’s be honest: AMC was betting that blood would be thicker than water. We’ll have to wait until the end of the movie’s run for a final verdict, but it looks like the Chinese are actually quite good arbiters of quality.

7) Do not try this at home. The irony of a government-sanctioned film commemorating a revolutionary response to injustice and oppression was not lost on the mainland Chinese audience. If anything, though, the irony serves more as a reminder of the government’s power than as motivation for demanding reform. Still, the first step towards legitimizing a social movement is to glamorize it: the government should be careful what it wishes for.

To get you in the mood for number 8:

8) The East is Red. In a desperate attempt to regain political clout ahead of China’s imminent leadership transition, “Chinese JFK” Bo Xilai instituted a campaign to revive Red culture in Chongqing, where he is mayor. The charm offensive directed at Beijing includes sing-a-longs to Red songs, Red song singing competitions, and readings of Mao’s poetry.

Surprisingly, not everyone is laughing. It turns out there is significant nostalgia for the days of Chairman Mao, not because anyone longs for famines or the Cultural Revolution, but because there is something about Red culture that the Chinese feel proud to claim as part of their DNA. The revolutionary impulses in the film that the government is trying to promote and suppress at the same time have free expression in Red songs. This is true for many people in mainland China, but all the more so for the workers and peasants that are the songs’ heroes. Chairman Mao rose to power off of the widespread anger and fatigue of the working class—perhaps his rehabilitation is not so much an exhortation for the newly wealthy Chinese to remember his ideas as it is a reminder that his ideas have not been forgotten by the CCP. Altogether, now:

“On China,” by Henry Kissinger

May 22, 2011 § 1 Comment

By Rebecca Liao

As expected, Kissinger ends his relative quiet on a major foreign policy issue with a treatise. Taking bets now that Christopher Hitchens will be ready with a scathing review in Slate, or even Vanity Fair, by the end of the week.

The Chinese have a very dark sense of humor

May 2, 2011 § 2 Comments

By Rebecca Liao

In response to the death of Osama bin Laden, the following parable went viral on the web in China:

Al Qaeda once sent five terrorists to China: One was sent to blow up a bus, but he wasn’t able to squeeze onto it; one was sent to blow up a supermarket, but the bomb was stolen from his basket; one was sent to blow up a train, but tickets were sold-out; finally, one succeeded in bombing a coal mine, and hundreds of workers died. He returned to Al Qaeda’s headquarters to await the headlines about his success, but it was never reported by the Chinese press. Al Qaeda executed him for lying.

Read more from Evan Osnos here.

Those Wise Restraints that Make Men Free: Legal Reform with Chinese Characteristics

May 2, 2011 § 1 Comment

By Rebecca Liao

Since the late 1930s, the President of Harvard University grants degrees to the graduating law school class with the following exhortation: “You are ready to aid in the shaping and application of those wise restraints that make men free.” The quote comes from John Maguire, professor at Harvard Law School from 1923-57; it is also on a plaque in the main stairwell of the law library in the hopes that graduation day would not be the fist time students came across the idea. At first blush, “wise restraints” seems to simply be a more poetic name for law. If law school and legal practice teaches us anything, however, it is that the law is much more than its ostensible elements because it is very rarely clear. It is an infrastructure based on words and renovated with only partial visibility of the existing structure. Since the law is not self-evident and self-supporting, it relies on other sources to identify what it is: yes, history and divination of intent are popular, particularly on the United States Supreme Court, but lower courts more commonly look to “policy,” which is just shorthand in the legal profession for the social goals behind enactment and implementation of the law, how the law should relate to others in its space, and, more fundamentally, the social and moral values the law touches upon. These are the “wise restraints” on the operation of a society—law is merely their codification. For a society in which the rule of law is taken for granted, they serve a chiefly utilitarian purpose, their influence on law is incremental and most evident in the outcome of cases. For a society just building the rule of law, there is no buffer between them and how that society is run. Defining these “wise restraints” therefore becomes a frequent and essential exercise.

The People’s Republic of China embraces restraints, many of them wise. A religious devotion to economic growth has facilitated an equally expansive development of corporate law. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP)’s public relations campaign releases prominent dissidents, such as lawyer Xu Zhiyang, under guarantee, which allows them to leave police custody while their movements are monitored for about a year. Labor unrest, one of the most potent challenges to stability and government legitimacy, is often the most successful form of protest: the Shanghai truckers who blockaded one of China’s largest container ports two weeks ago in anger over high fees and gas prices won fee concessions from Shanghai authorities without encountering riot police. Posters in major cities encouraging people to not spit and litter and the inelegant, piecemeal adaptation of foreign criminal procedure are both part of the Chinese drive to further modernize and self-improve. Though less visible, a flourishing publishing industry and rise of the avant-garde artist community, untouched by censors, have placed China squarely in the mix of the international intellectual conversation. Above all, the Chinese are consensus-minded. The government’s recent espousal of “harmony” touches a deep chord in Chinese relationships, from the family unit to the individual’s interaction with the state: peace and stability at all costs, happiness and contentment not required. None of these “wise restraints” have done their job perfectly, but they exist and are permanent residents, at least for the time being.

Interestingly enough, the statue of the philosopher who popularized the idea of social harmony was removed from Tiananmen Square two weeks ago, after a mildly controversial four-month stay. While few in China disagree with his teachings of ethical behavior, respect for elders and obedience to authority, Confucius ran into trouble with Chairman Mao, who blamed his “everything in its place” philosophy for China’s pre-Liberation feudal system. Confucius has enjoyed a revival since the rejection of Maoist ideology, but placing a 17-ton statue of his likeness across from Mao Zedong’s portrait was too much for a few influential leaders in the Central Party School. As a symbol of China’s imperial past, Confucius is understandably as passé for the Chinese as the hutongs in Beijing that are making way for modern buildings.

What the party leaders surely realize, though, is that Confucianism has never been, and never will be, a trend. Its ethical and cultural teachings are part of the Chinese DNA. If the leaders are looking to reform a country and claim credit, they ought to learn from someone who has experience leaving an indelible and beneficial ideological imprint.

Confucius and his contemporaries from the Hundred Schools of Thought worked during the turbulent Spring and Autumn Period and the Warring States Period, both fraught with fierce political struggle and regional warfare. That intellectual output flowered when survival was the prime concern is curious. During such bleak periods, ideas about social order tend to fall into the freedom or order camps—a very practical and quick system for finding solutions to urgent problems. What the philosophers of this period were able to do was reframe the problem from one of finding “wise restraints” designed to increase the chances of survival to “wise restraints” that promote far more important ideals. Both approaches have the same goal: a harmonious society, but the latter aims to put in place a mechanism that pays dividends over the long term instead of reacting to immediate concerns based on the instinct for self-preservation. Modern China and the CCP are entering the phase of development in which the long-term perspective is the only one that makes sense.

For all the stratospheric annual growth rates and whispers of a new superpower, it is important to remember that China was able to achieve both through near uninhibited capitalism. The income gap has, as a result, increased well beyond sustainable levels, and the name of the game in Chinese society is survival. Most Chinese citizens work incredibly hard and sacrifice an inordinate amount, only to be deprived basic needs such as education, health care, and sanitary living conditions. Their efforts are the baseline necessary to tread water; upward social mobility further requires backdoor dealings and ruthless competition, both of which are manifest in the rampant corruption in governmental entities and corporations. Economic development has afforded Chinese citizens more contact with the outside world, and their sophistication and frustration are estimable challenges to the stability of the country and the legitimacy of CCP rule. Between addressing social problems and quashing dissent, the latter is the far easier short-term solution. The CCP’s paranoia over the false alarm that was the “Jasmine Revolution” revealed a fragile and unsteady psychology behind its displays of power. As is the case with many in China, the party’s position is at once enviable and precarious.

Even the staunchest free-marketeers will admit that laissez-faire does not preclude the rule of law, for law is meant to quell the rage of survivalist instinct. The arbiter of these laws is different depending on the narrative of social relations. Let’s start with one more palatable to the Chinese government: in a Hobbesian worldview, the benevolent dictator ensures order and prosperity for his subjects. In order to be effective, this dictator needs to be rational in the economic sense, maximizing self-interest while realizing that happy citizens are in his best interest. The catch is this: a rational dictator should discover at some point that absolute power corrupts absolutely, not just in terms of its effect on personhood, but because it maintains the illusion that it exists. Absolute power is a fantasy with a short shelf-life. It eventually isolates the dictator to the extent that he loses touch with reality. To maintain his efficacy, he needs to first subject himself to a mechanism for keeping abreast of the state of things and how best to address them. That is, he has to admit the limits of his knowledge and authority to absorb a necessary diet of new ideas.

If the end game sounds a lot like a system of checks and balances, it is. While unthinkable on a macro level, the Chinese government has begun to implement such a system in certain pockets of the law, most prominently in criminal procedure. The recent crackdown on human rights lawyers, artists and other political activists has demonstrated, however, that where such procedures have been imperfectly drafted, no attempt has been made to amend them, and where they provide for police discretion, judgment calls are never challenged or reviewed.

Ai Weiwei’s detention is a good example of these shortcomings in the pre-trial phase of prosecution. Ai has been in detention for nearly a month now without any notification of his whereabouts or the specific charges leveled against him. The Criminal Procedure Law states that a person may be held for up to thirty days only in limited circumstances. Notice of detention is not required if the police believe that it would interfere with their investigation. Despite assurances by the Lawyer’s Law that suspects have the right to meet with their attorneys without exception, the CPL allows investigators to prohibit such a meeting if the case involves “state secrets”. Invariably, the police find all exceptions applicable in sensitive cases of a political nature. Neither the judiciary nor the procuracy (prosecutors) are able to review these decisions.

In the case of lawyer Li Zhuang, who had been sentenced a little less than two years ago for “lawyer’s perjury” (encouraging a client to give false testimony) and tried again last month for enticing a witness to fabricate evidence, his appearances in court strongly suggest that the judge, prosecutors, and police acted in concert to ensure a guilty verdict. In both trials, no live witnesses were called—the only evidence was written witness statements, which cannot be cross-examined to test for veracity or coercion. During the sentencing phase of the first trial, Li angrily yelled out upon receiving his sentence that he had been framed and was recanting his confession, leading many Chinese legal experts to believe that he had confessed under false guarantee of reduced jail time. The judge did not further investigate. Before Wen Qiang, Chongqing’s corrupt police chief, appealed his guilty verdict, Judge Wang Lixin, who presided in the trial, posted his diary to the official website of the Supreme People’s Court. In it were accounts clearly showing that trial prep responsibilities were being coordinated in meetings between himself, the attorney general, and the police chief that took place before the trial commenced.

A legislator, an enforcer, an interpreter—a robust system of law may not require all three roles, but it certainly requires all three perspectives. For how complete can the law be without someone to create and prune it, someone to clarify it, and someone to implement it? Where one or more perspectives are toothless, their adoption is the next step in developing the “wise restraints that make men free,” one level of abstraction above ingrained social values, one level below a self-governing system of laws that makes a benevolent and functional government possible. These restraints can only be established if a society trusts their potential to bring about growth and longevity. Reform must present a new face to a country unsympathetic to it. For the CCP, reform should be understood as a long-term strategy that works with reality, that realizes no state can be all-knowing without a means of outside education and improvement, and no lawyer can be cowed into silence for long.

Beijing Bob: Protester as Possum

April 13, 2011 § 7 Comments

By Rebecca Liao

Uninhibited exercise of free speech is a useless fantasy. Two Sundays ago on Meet the Press, Senator Lindsey Graham gave the following unfortunately-worded condemnation of Terry Jones’ burning of the Koran in Florida: “I wish we could find a way to hold people accountable. Free speech is a great idea, but we’re in a war.” The “fighting words doctrine” in US constitutional law recognizes that words that can only inflict injury or immediately incite violence are not protected under the First Amendment. Those are just some of the officially-sanctioned restrictions on free speech. Then there’s the social filtering that Carolina Herrera put best in her Proust Questionnaire for Vanity Fair: when asked when she lies, she answered, the ellipses emphasizing the obviousness of the response, “Whenever I have to…it’s called manners.” Social activists worth their salt would never worry about being rude, but that is not to say they do not have a keen instinct for expedient self-censorship.

For an iconic voice of the protest generation, Bob Dylan doesn’t talk very much. In concerts, he only speaks to introduce the band members. His interviews are really only quotable if questions are included, just to give a sense of how frustrating and hilarious his stubbornly non-sequitur answers can be. More importantly, Dylan never says what the listening public wants or expects him, of “Blowin’ in the Wind” and “The Times They Are a-Changin” fame, to say. The seeming disconnect between the person and the personality is pronounced to the point that many still have a hard time believing it exists, which leads to misguided outbursts as newsworthy as the episodes that inspire them. In reaction to Dylan’s performing in China according to a setlist pre-approved by the Ministry of Culture and failing to voice support for detained artist Ai Weiwei, Human Rights Watch had a go at the singer, as did the New York Post and John Whitehead at HuffPo. In the end, though, it was Maureen Dowd who really did Beijing Bob proud with a scathing op-ed in the New York Times:

The idea that the raspy troubadour of ’60s freedom anthems would go to a dictatorship and not sing those anthems is a whole new kind of sellout — even worse than Beyoncé, Mariah and Usher collecting millions to croon to Qaddafi’s family, or Elton John raking in a fortune to serenade gay-bashers at Rush Limbaugh’s fourth wedding[…]

Dylan said nothing about [Ai] Weiwei’s detention, didn’t offer a reprise of ‘Hurricane,’ his song about ‘the man the authorities came to blame for something that he never done.’ He sang his censored set, took his pile of Communist cash and left.

Dowd does eventually acknowledge Dylan’s reluctance to be a protest figure, but rather than accept that as an explanation, let alone an excuse, for his refusal to be overtly topical, she suggests that he was a cynical sell-out from the very beginning, leveraging the fertile socio-political culture of the 60s to become famous, only to cut and run once he had succeeded. It’s a fair, but nauseatingly demanding, point that, as Alex Ross, classical music critic for the New Yorker, said over the weekend, smacks of “the worst sort of armchair moralism”. Given the body of work sung in place of the anthems Dowd so wanted to hear, among them “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall,” “Gonna Change My Way of Thinking,” “Like a Rolling Stone,” and “Desolation Row,” it’s also a lazy and unprofessional point that was probably conceived and written before Dowd had done any fact-checking (i.e. looked up the list of songs performed). So what she and her fellow critics hated wasn’t exactly what Dylan actually did in China so much as the very idea that he would go there and not be Yankee gangbusters.

This is the exact kind of narrow, inflexible, commercial-friendly generalization Dylan ran away from when he was first anointed a visionary and brave folk singer. Direct criticism is not the only way to effectively make a point. Dylan’s songs largely shy away from proper references; they instead work by playing off the atmosphere in which they are performed. They will always be associated with the events and spirit of a certain era, but someone with no knowledge of their history will find that the lyrics, inflections and chord relations are actually quite well suited to counterculture tendencies in any socio-political landscape.

If anything, Dylan’s decades-long slide into the uncooperative eccentric has further enforced the subversive nature of his work. It began innocuously with altered melodies and transposed lyrics. It graduated to a game of cat and mouse with the press generally and, as Paul Williams put it, “cause-chasing liberals who concern themselves with the issues and have no real empathy for people” in particular. If people insisted often enough that a song had a certain significance despite Dylan’s denial, he would give in and make up a clearly bogus backstory. At some point, the artist became unrecognizable, his delivery in concerts as unpredictable in quality and substance as only the most die-hard Dylan and music-legend fans would tolerate. Whether these are the tricks of a calculating fameball, a tired performer, or just an artist that has refocused his perspective is not clear. What is evident, though, is that Dylan is not comfortable being in anyone’s corner, neither that of William Zantzinger nor Hattie Carroll’s champions. It leads to a funny outcome in which the message of the music maintains its clear bent but remains almost universally claimable because it refuses all allegiances.

More importantly, it’s the sort of “protest” that goes over well in China. The Ministry of Culture allegedly did screened Dylan’s setlist, but lyrics like the following from “Gonna Change My Way of Thinking” slipped past:

Gonna change my way of thinking

Make myself a different set of rules

Gonna change my way of thinking

Make myself a different set of rules

Gonna put my good foot forward

And stop being influenced by foolsSo much oppression

Can’t keep track of it no more

So much oppression

Can’t keep track of it no more

Sons becoming husbands to their mothers

And old men turning young daughters into whores

As did this gem from “Desolation Row”:

Now at midnight all the agents

And the superhuman crew

Come out and round up everyone

That knows more than they do

Then they bring them to the factory

Where the heart-attack machine

Is strapped across their shoulders

And then the kerosene

Is brought down from the castles

By insurance men who go

Check to see that nobody is escaping

To Desolation Row

Chances are the Chinese officials didn’t see a “Free Tibet” riff on the program and let it go. It’s also plausible that the Chinese government categorically likes Dylan’s music: CCTV played “Blowin’ in the Wind” in the background for their feature on him. One man’s protest song is another man’s…protest song, equally applicable against Communist regimes and Imperialist barbarians.

Contrast that with Ai Weiwei, who makes both his political activities and the identity of those on the receiving end clear. On the eve of the Beijing Olympics in 2008, for which he helped conceive the Birds Nest Stadium, Ai wrote a column for The Guardian entitled “Why I’ll stay away from the opening ceremony of the Olympics”. It included the following statements:

Almost 60 years after the founding of the People’s Republic, we still live under autocratic rule without universal suffrage. We do not have anopen media even though freedom of expression is more valuable than life itself […]

We must bid farewell to autocracy. Whatever shape it takes, whatever justification it gives, authoritarian government always ends up trampling on equality, denying justice and stealing happiness and laughter from the people.

Ai has reiterated these sentiments in his blog, twitter feed, and interviews with foreign press on a regular basis. He isn’t simply a pundit, though: after the devastating earthquakes in Sichuan province, Ai created an installation for the Haus der Kunst in Munich comprised of 9000 children’s backpacks spelling out, “She lived happily for seven years in this world,” words from a mother who lost her child. Assembling a group of volunteers through the Internet, Ai compiled a list of 5,335 names of children who had been crushed in the rubble. All went to 20 schools whose buildings had collapsed during the quake. Though the government shut down the investigation, it launched one of its own into shoddy classroom construction.

Like Dylan, Ai is an increasingly subversive artist, but their styles could not be more different. In an interview with the Financial Times a year ago, Ai confessed, “You play like a gambler. You may be on a winning streak. You may think: ‘This is a winning table’. And you may fantasize that you can win for ever.” One man has sung his ballads for 60 years; the other has been silenced, hopefully not indefinitely. It would be indefensible to downplay what Ai has sacrificed for his political bravery, but it would be just as irresponsible to encourage him to continue as he has and permanently join the leagues of “crazy, anti-China dissidents” the Chinese public by and large ostracizes. Protest works against a very organized and controlled enemy; it should be just as inclined in order to maximize effectiveness.

Ai’s work is already a powerful tool: regarding his Circle of Animals/Zodiac Heads, Ai explains, “My work is always dealing with real or fake, authenticity, what the value is, and how the value relates to current political and social understandings and misunderstandings. I think there’s a strong humorous aspect there.” Whether by dropping a Ming vase, giving the middle finger to the world’s most recognizable monuments, or decapitating zodiac signs, an irreverence that makes people laugh along with it without causing discomfort is the most untraceable text message.

When Ai Weiwei is released, and he will be released because the Chinese hate more than anything to lose face, he should, as Dylan has, do his job. At the end of the day, we all just work here.

Preview: Ai Weiwei’s Circle of Animals/Zodiac Heads

April 6, 2011 § 1 Comment

By Rebecca Liao

Unveiled at the São Paolo Biennale in Brazil in September, 2010, Circle of Animals/Zodiac Heads by China’s foremost contemporary artist Ai Weiwei will begin its international tour at the Pulitzer Fountain at Grand Army Plaza near Central Park and the Plaza Hotel. Circle of Animals/Zodiac Heads is based on the fountain clock at Yuanming Yuan, an 18th-century imperial retreat outside Beijing, and is Ai Weiwei’s first major public sculpture. Commissioned by Emperor Qianglong of the Qing dynasty from two European Jesuits serving in his court, the clock featured the heads of the twelve animals in the Chinese zodiac spouting water every two hours. In 1860, the Yuanming Yuan was ransacked by French and British troops, and the heads were pillaged. Early 2009, the heads depicting the rabbit and rat were auctioned off by Christie’s as part of Yves Saint Laurent’s estate despite vehement objections from the Chinese government and advocacy groups. (Wealthy art collector Cai Mingchao ended up sabotaging the auction by posting the winning bid and then refusing to pay.) Today, five other heads – the ox, tiger, horse, monkey and boar – have been located; the whereabouts of the other five are unknown.

Four feet high (10 feet when the base is included), three feet wide, and 800 pounds, Ai Weiwei’s heads are far from replicas of the originals. He explained it this way to AW Asia, “My work is always dealing with real or fake, authenticity, what the value is, and how the value relates to current political and social understandings and misunderstandings.” (Full interview)

Sunday morning, officials in China detained Ai Weiwei as he attempted to board a plane bound for Hong Kong. His wife, nephew, and a handful of his employees were arrested and questioned as well. The US, UK, France, Germany, and the European Union have since called for his release. Officials in China remain steadfastly silent on his whereabouts.

Circle of Animals/Zodiac Heads will be revealed in New York as planned on May 2–one day after May Day.

In the meantime, here is a preview of the sculptures. Throughout the turmoil, we shouldn’t forget that ultimately, Ai Weiwei views the exhibition as “an object that doesn’t have a monumental quality, but rather is a funny piece.” (If you place your cursor over an animal’s image, its characteristics will pop up. All images are courtesy of AW Asia.)